The Ocean's Ticking Time Bombs: Offshore Oil and Gas Expansion and Our Climate Future

As world leaders gather in Belém for COP 30, Brazil faces a contradiction – hosting urgent climate negotiations while simultaneously pursuing aggressive offshore fossil fuel expansion. It's a tension that has become woven into recent climate conferences, and one that demands honest scrutiny. Brazil's situation offers a particularly stark lesson about the hidden costs of our continued dependence on offshore oil.

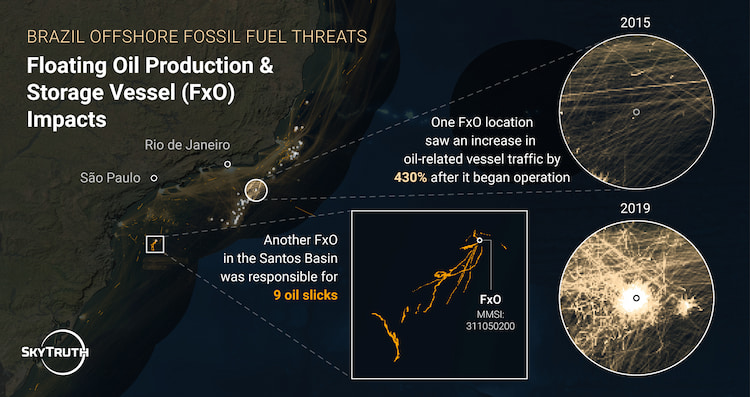

Satellite imagery reveals what often goes unseen in discussions about offshore oil development: chronic pollution that receives little public attention. Our recent investigation into Brazil's offshore fossil fuel operations documents this pollution and identifies a particularly troubling source: floating production, storage, and offloading units, or FPSOs. Along with FPSOs, floating storage and offloading, floating liquefied natural gas, and floating storage regasification units (collectively FxOs) are all vessels stationed offshore for use in oil and gas extraction and production.

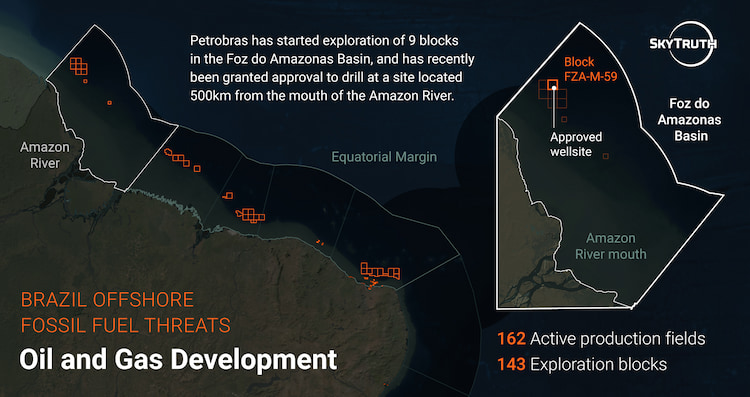

As a cheaper alternative to traditional oil platforms for developing deepwater fields, these massive vessels represent a booming segment of global offshore oil infrastructure. Yet they're emerging as some of the industry's most problematic assets: earlier this year, SkyTruth published a global investigation that found FxOs – despite being a small fraction of offshore infrastructure – account for four of the ten most polluting assets globally, linked to at least 216,000 gallons of oil slicks and major flaring and vessel-emissions burdens, based on a conservative analysis of satellite imagery between June 2023 to October 2024. In 2011, an FxO operated by Shell off the coast of Nigeria spilled more than 1 million gallons of oil during a botched transfer operation. In Brazilian waters alone, we documented 179 probable oil slicks since 2017, with 48 tied directly to oil and gas infrastructure, including 27 associated with FxOs. This is occurring as Brazil's offshore production has surged 49% and vessel traffic has increased 81% in recent years.

Brazil has been at the forefront of FxO development since deploying one of the world's first in the Campos Basin in 1979. In 2025, nearly 100 oil platforms and 40 to 60 FxOs were operating in Brazil's Exclusive Economic Zone, according to data from Global Fishing Watch and SkyTruth. Far from slowing down, Petrobras plans to increase both the number of FxOs and their efficiency, with Brazil's fleet continuing to expand to meet ambitious production targets.

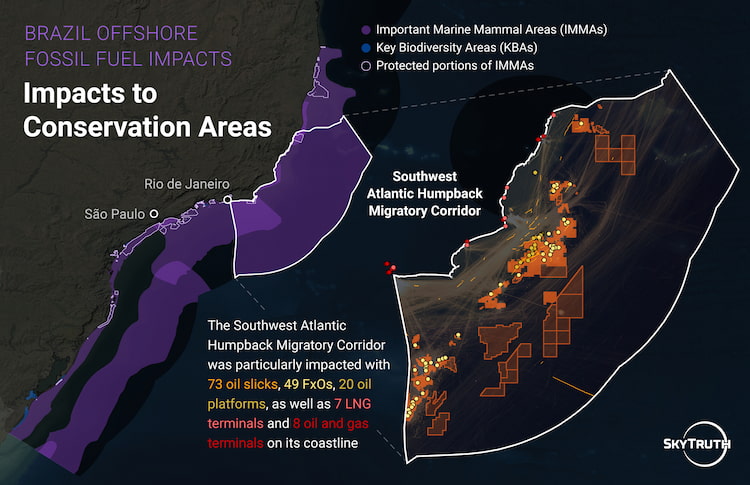

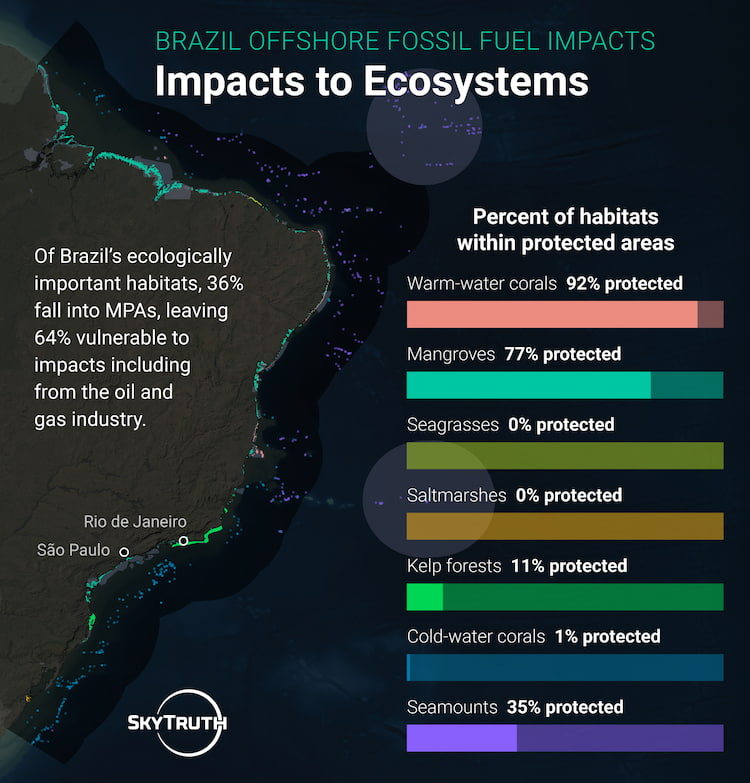

What makes this particularly concerning is where this expansion is happening. Brazil's offshore oil and gas blocks include some of the world's most ecologically sensitive areas – mangroves that protect coastlines, coral reefs struggling against ocean warming and acidification, and critical marine mammal habitats. SkyTruth’s investigation found 49 FxOs stationed within the Southwest Atlantic Humpback Migratory Corridor.

In addition, these ecosystems provide critical services: mangroves, seagrasses, and salt marshes are what scientists call "blue carbon assets" – natural systems that absorb and sequester carbon, helping to mitigate climate change. Destroying these habitats to facilitate coastal energy infrastructure undermines the very climate solutions we desperately need.

The pollution problem extends beyond the FxOs themselves. Commercial shipping has become a chronic stressor in Brazil's waters, and much of what we observe is likely intentional oil pollution – vessels discharging oily wastewater, a practice that's been occurring for decades despite international treaties restricting it. This vessel pollution stems partly from ships burning heavy fuel oil – the dirtiest, most climate-polluting fuel commercial vessels use. Its thick, sludgy residue creates oily bilge waste that far too many vessels then illegally dump into the sea. Addressing vessel pollution also demands international cooperation, as perpetrators typically fly “flags of convenience” with countries imposing minimal oversight.

Brazil's situation crystallizes a broader truth: the same oil being produced in the Santos Basin to power the global economy is fueling the climate crisis that threatens the Amazon rainforest so many Brazilians depend on. Expanding oil and gas development and FxO deployment in ecologically sensitive zones trades short-term production gains for long-term environmental losses that will be difficult, if not impossible, to reverse.

And yet, COP 30 presents a high-profile possibility for leadership. Brazil has the opportunity to demonstrate how a major oil-producing nation can reconcile economic development with marine stewardship. The country could lead by establishing mandatory continuous monitoring requirements for all FxOs and other oil and gas facilities operating in its waters, using satellite-based systems to detect oil pollution and emissions in real-time. Brazil could also pause the construction of new coastal oil and gas infrastructure in areas with critical blue carbon habitats, while imposing stricter pollution penalties that actually deter violations. Development banks financing offshore projects could reinforce this leadership by requiring comprehensive environmental monitoring and transparent public reporting of pollution incidents and emissions data.

Most fundamentally, Brazil could signal a new direction by committing to no new offshore oil and gas leases in ecologically sensitive areas, safeguarding ecosystems that provide climate, biodiversity, and economic benefits far beyond any fossil fuel revenues. Phasing out the use of heavy fuel oil would further reduce chronic oil pollution. And as COP 30 host, Brazil is uniquely positioned to advocate for stronger international cooperation to hold polluters accountable, ensuring all nations share responsibility for protecting the world’s oceans.

These aren't abstract policy suggestions – they're achievable steps that would address the specific pollution sources we've documented. Our investigation represents just the beginning. SkyTruth will continue monitoring pollution from FxOs and platforms, habitat destruction from coastal development, and the cumulative effects on global marine ecosystems, making what used to be invisible ocean pollution visible for informed decision-making. The next chapter depends on collective action to match that visibility with accountability.

Discuss this article

Clicking links may earn us commission. . Stock images by Depositphotos.

Subscribe: Stories about wildlife, habitats and heroes

Welcome to Conservation Mag where we celebrate nature preservation through ecotourism and wildlife travel while we look for ways to preserve our heritage by supporting nature conservation. Starting conversations about the positive action people like you and I are taking to make a change.

Quick Links

Work With Us

![]()