“It must be terrifying,” muses the young man in the camo uniform. Strange words from someone with a 9mm on his hip. He continues: “I’ve actually tried to imagine what it must be like to be a poacher in the bush who suspects there’s a stopper group out there in the dark, looking for you.”

The conversation unfolds at a non-descript location in the bush of Singita within the expansive Sabi Sand Reserve. Having set up the interview with a representative of the local anti-poaching unit, our field guides were directed to this point along a sandy track. For a few moments, we watch another dramatic sunset. Silhouettes against the headlights intensify the atmosphere.

Apparently, that fear expressed by our interviewee has paid dividends for two neighbouring landowners in this region of Mpumalanga. As operators of lodges adjoining the Kruger National Park, their success in nature conservation is something they are deeply invested in – morally and financially.

I say “apparently” because anti-poaching units are purposefully vague about publicising details of operations. After yet another apology for not being able to answer a particular question, my interviewee offers Sun Tzu wisdom around keeping yourself hidden from your enemy.

Still, a rolling contract does give credence to the claim of this unit’s “no incident of rhino poaching in our area in six years”. Earlier, Singita GM Grant Oliver had also mentioned the poaching unit having done “a very good job” in drastically reducing the poaching stats since the bloody peaks of 2016.

Interview with anti poaching unit member

What the interviewee – operations manager at K9 SSS – does say is that some years ago, landowners of the Sabi-Sand Reserve opted to separate internal reserve security and the overall perimeter security of the region. “Singita went a step further and it was joined by its northern neighbour, Othawa Private Game Reserve, in choosing to appoint an independent anti-poaching operator. The anti-poaching job on these properties is now our responsibility,” he explains.

He prefers not to discuss the size of the area they cover, the size of the team, or even numbers of rhinos. He does however mention that there is escalating, and intensifying poaching pressure now being experienced within the greater Sabi Sand region.

“Rhino poaching is the main problem here,” he says. “Typically, rhino poachers move around in groups of between two to six people. Loners are rare.

“There is always one poacher in a group with a high calibre rifle, whilst others in that same group are armed with pangas and axes. Apprehending people in the latter cases is more difficult because the law pertaining to the use of deadly force by a private person is applicable to an anti-poaching unit too. Simply put, one may only use deadly force if your life is under threat. I am required to use comparative force. If someone comes at me with a spear or panga, shooting is permitted only when all other attempted remedies are proven to have failed.”

We linger on this topic of law for a bit and my source echoes what many South Africans have come to appreciate. “It’s not the law that’s the problem, but the application thereof.

“Cases often fall down due to technicalities because rules aren't followed. I do think there could be more stringent penalties for convicted poachers, but often it's about people not applying the laws and procedures properly when arrests are made,” he says.

The K9 SSS field rangers all carry quick reference cards that prompt specific, step-by-step action to ensure the best result should a case go to court.

Short on more detail, he goes for context.

“We’re an anti-poaching unit with a critical value-add in the form of our K9 dogs,” he explains. “We have field rangers that do the basic patrols and regular detection groundwork and have dogs that can then rapidly follow up for tracking and detection of say, firearms or ammunition.”

They are also trained to “apprehend a suspect” through “bite work”, although the operation deliberately avoids emphasis on this element in the dogs’ application. “You don’t want the animal to get used to relying on what they see. They’re more effective when they rely on what they smell.

“And smell is certainly more effective than sight, which is why dogs are more adept at rapid tracking than humans.”

A variety of breeds are used. Luna, the four-and-a-half-year-old hound the handler has brought along for display, is a Belgian Malinois. Dutch and German Shepherds as well as Spaniels and Bloodhounds are also used in this kind of work, although each has its speciality. Dogs are also trained to work with various handlers, which provides more efficient continuity when there are staff changes.He mentions that some other anti-poaching operations occasionally make use of packs of dogs, which are released on the trail of poaching suspects and then followed by helicopter.

Other essential tools of the trade have been the presence of good fencing, which allows for the efficient detection of infiltration; intelligence; and in-field technology.

Where intelligence gathering is concerned, it is a component of the fight he says, but is run by a separate organisation – Sabi Sand Management. “It makes its way to us because all the players in the fight collaborate. Where the information comes from however, is received as in any security environment – on a need-to-know basis only.”

As for technology, it’s “a good tool, if you use it correctly”.

“We have thermal monocular for night-time detection and a drone with exceptional thermal capability too. It helps tremendously during gunshot reports because carcasses, live rhino and poachers can be invisible to the naked eye at night.

“Camera traps have also helped a lot. They don't always result in arrests, but they do occasionally help as a deterrent of further action. Cameras serve as early detection and sends signal to the control centre , which could ultimately save a rhino.”

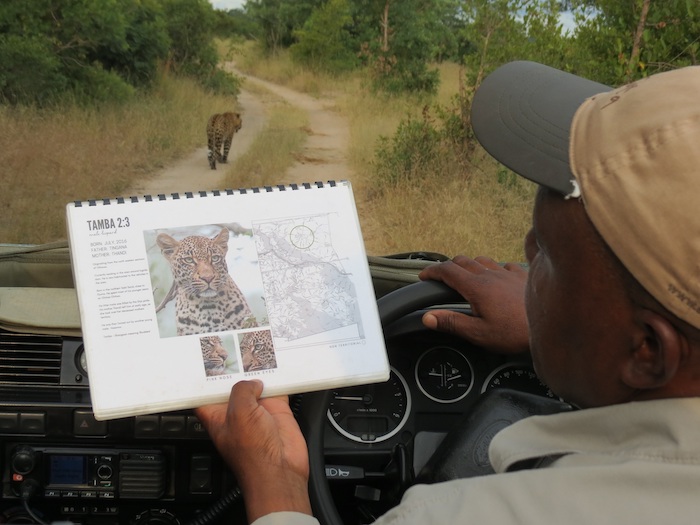

Part of conservation efforts includes keeping detailed records of wildlife encountered

K9 SSS uses a camera trap equipped to immediately transmit images taken. “If it doesn't send, it's useless to us. It doesn't help if images are collected two days later because the poachers will be long gone.”

Equally important to the fight across this vast space is to study general behaviour. “Studies have shown that the landscape will most often determine the routes a person will follow in an environment. If you know and can read the land, then you have an advantage over anyone moving through it.”

The question arises: how technologically sophisticated are poachers?

“I've heard of smartphones found on scenes, but that's quite rare. Reports of drones haven't been confirmed. What I can say is that poachers are organised and are good at planning operations. There's a reason they're as successful as they are.

“When I discuss our work during education outreaches, people just want to hurriedly fix the problem. That's not going to work. You need people with good bush expertise applying skills to the problem because our opponents are very, very good.”The fight is also ever-evolving. “For example, when this problem began, poachers walked barefoot.

He discards the perception of poachers as family providers in a desperate situation. “In my experience, this is highly organised crime. These are syndicates comprised of individuals who are not taking care of families nor are they down on their luck. A type of ‘subsistence’ poaching may exist, but it’s not what we are seeing. It’s about big money for criminal organisations for which poaching is simply one division.”

Here, I steer the conversation to the job of taking on poachers. My source says he arrived in this position through a love of the bush. He started as a field guide at a lodge but changed direction when a friend invited him to a scene where a pregnant rhino cow had been killed. He volunteered for their anti-poaching unit and abandoned guiding completely in 2017 to do this full time.

He describes the fundamental make-up of a field ranger as someone with a fascination with the bush because the hours are long and often filled with solitude; and, good tracking ability.

When there is nothing happening, however, he revels in his bush time. “We are often stationed at observation posts and one of these occasions was particularly memorable. I like my coffee, so I have a Stanley press-and-mug in one that I always take along for that midnight morale booster.

“During the course of those early hours, I used the thermals to pan the area before taking some coffee, but something nagged at me. I lifted the thermals and panned again to suddenly see, just 50m from my position, an entire pride of lion watching me.

Fortunately, all ended without incident. “We’re trained to observe the situation and to react when necessary. It became clear to me the lions were curious but weren't stalking me. They eventually moved on.”

About tracking, he says: “It’s not something you can learn from a book; it requires constant practice and not many people are good at it.

“All other tools – the dogs, the technology – are secondary to those characteristics of passion and ability.”

There are several other insights that have helped to underscore their success. For example, when hiring, the unit seeks out rangers who are not familiar with local communities as intimidation by crime syndicates is rife and these syndicates are always looking for insider help.

In addition, ex-military people don't automatically do well in this job, my source says. “Bush skills are rare, and they have different approaches to operating in these environments. Conventional warfare and anti-poaching are very different.”

The fight against rhino poaching may be a war, but there’s clearly more to it for those working in anti-poaching. “On our end, we're essentially treating a symptom and not the cause. I fear that by the time the market demand for horn is dealt with, it will be too late for the rhino. If something doesn't drastically change in the next 10 years, you're really going to struggle to see rhino in areas like this.”

“I fell in love with the bush when my father first took me to the Kruger National Park as a child. The numbers of rhino in this region now are nothing compared to what they were back then.

“If we lose this fight, we all lose,” he says

Different kinds of mesh are being tested in order to protect trees from elephant damage

Other highlights of the Singita approach

One of several lodges in the Sabi-Sands region, Singita has become renowned as a leading conservation and ecotourism brand. It wasn’t always that way. My guide, Piet Marimane, grew up in a village nearby and recalls the hunting that pervaded the region in the mid to late 1970s. That was before the large farms were integrated into the Kruger National Park.

With the investment of Singita founder has come dramatic change beyond mere lip-service in advertising campaigns. Its first lodge, Singita Ebony, opened in 1993 although the story dates to almost a century ago with land acquired by the grandfather of the founder, Luke Bailes. Over time, what was a hunting concession was transformed into a comprehensive conservation reserve.

Furthermore, the Singita brand extends to several lodges in four African countries - all espousing a 100-year commitment to safeguarding the wildlife and communities where they operate. Amongst other activities, the Singita Lowveld Trust raises funds to support the anti-poaching and canine unit.

Singita’s ethos is visible in a myriad of small things. On our drive through the reserve around Ebony, Piet points out wire mesh around the base of marula trees. There are different types – each an attempt to find a solution that protects the tree from having its bark stripped by elephant without interfering with other species, such as leopards that might want to climb.

At the lodge, guests are informed that linen bedsheets aren’t stone-washed for the environmental benefit it brings. Panama-style hats are made of paper; cocktail straws are re-usable metallic rather than plastic; and, in August last year, Singita initiated a levy that guests pay to off-set the carbon footprint of their stay.

Funds generated are used to purchase verified carbon credits from accredited service providers in each of the regions in which Singita operates. In South Africa, it’s the Climate Neutral Group’s Wonderbag project (VCS accredited).

Contributions to the Singita Lowveld Trust may be made via https://singita.com/conservation/projects/anti-poaching-canine-unit-sabi-sand.

A perspective on de-horning

My field guide was the first on this trip to mention the de-horning of rhinos, a practice to remove the prize that motivates poaching. A rhino carcass had been discovered with a fatal wound in its chest – the result of a natural altercation.

It illustrates the complexity of the issue.

Firstly, there’s free movement of rhinos between the properties of the many landowners of the various reserves, making any dehorning an arduous and drawn-out process. At the same time, there are many different perspectives on the practice too, highlighted for one by incidents as described.

For one landowner to resist the practice is futile, no matter how good the intent is. Properties with horned rhinos have been the target. As more animals are dehorned across the region, so the targeting of remaining areas of horned rhinos will intensify not only because of availability but because of higher prices accompanying the scarcity.