Understanding the social and ecological complexities of interactions between large carnivores and livestock farming communities is critical to conserving our natural heritage.

I’ve always been drawn to interdisciplinary research trying to address pressing issues of our time. How do we balance poverty alleviation and economic development, while allowing for coexistence with species competing with humans for habitat and potential prey? That’s how I ended up studying an MSc on the human-wildlife conflict at the UBC Wildlife Coexistence Lab. Human-wildlife conflict is a global phenomenon and a leading cause of large carnivore decline. Locally in British Columbia (B.C.), human-carnivore conflict occurs with black bears, cougars and wolves - but my research is 13,000km away in Sri Lanka, where conflict between cattle herders and the endangered Sri Lankan leopard (Panthera pardus kotiya), the terrestrial apex predator, will likely escalate unless we intervene in an appropriate way.

Camera trap photos of a male Sri Lankan leopard (Panthera pardus kotiya)

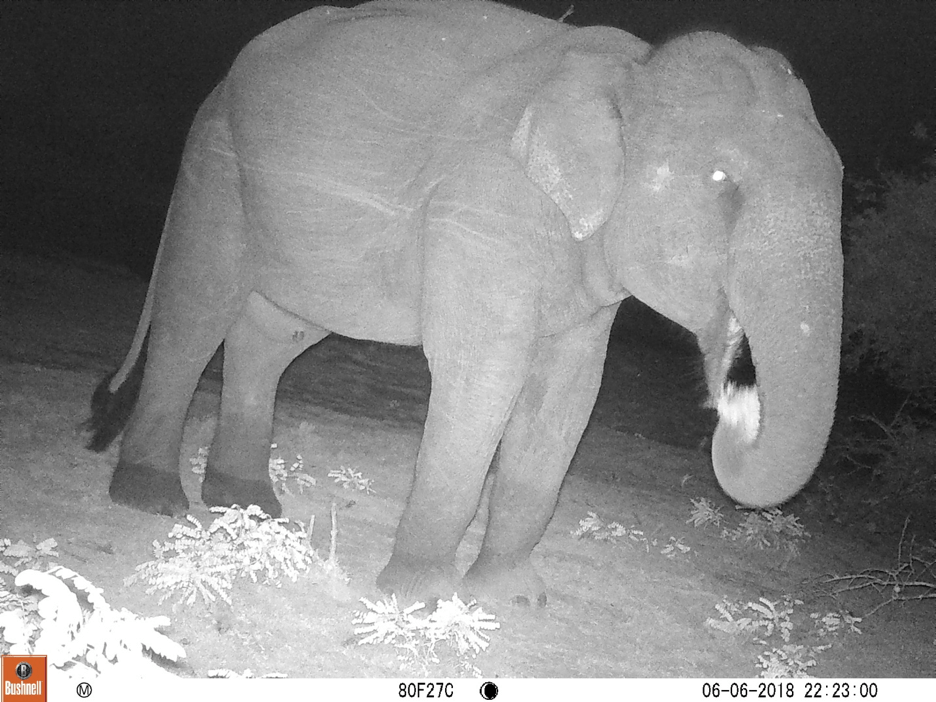

To understand the complexities of studying interactions between large carnivores and livestock farming communities, I believe we must address both the social and ecological aspects of the issue. One part of my work aims to identify predictor variables and their relative influence on resulting ‘conflict’ (level of livestock depredation by leopards) – specifically, native prey abundance, cattle density, husbandry techniques and distance to various habitat features (road, water, continuous and patch forest). Using tools such as remote camera traps, GIS and structured surveys, we can analyse these variables and identify potential conflict ‘hotspots’, thus informing the prioritization of limited resources available for conservation.

Wild boar (Sus scrofa cristatus) piglets are among the leopard’s common prey in this part of the country

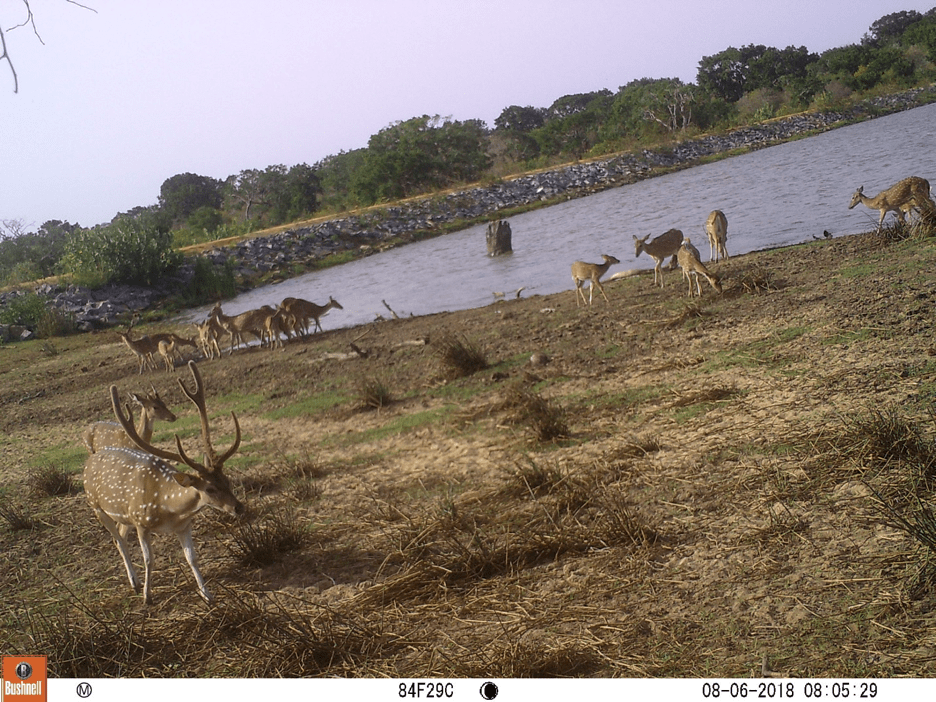

Spotted (or axis) deer (Axis axis ceylonensis) are also common leopard prey.

Another part of my work aims to address the social aspect of leopard-livestock conflict, using surveys to measure attitudes towards a) leopards, and b) willingness to adopt different mitigating husbandry practices against predictor variables such as socio-demographics, cattle demographics, limitations, costs, knowledge and experience. What we may hypothesize as being an intuitive relationship (e.g. those that bear more direct costs from losing livestock will have negative attitudes towards leopards) may not be true in this local context, illustrating the need to include this aspect into more human-wildlife conflict research and let the results speak for themselves.

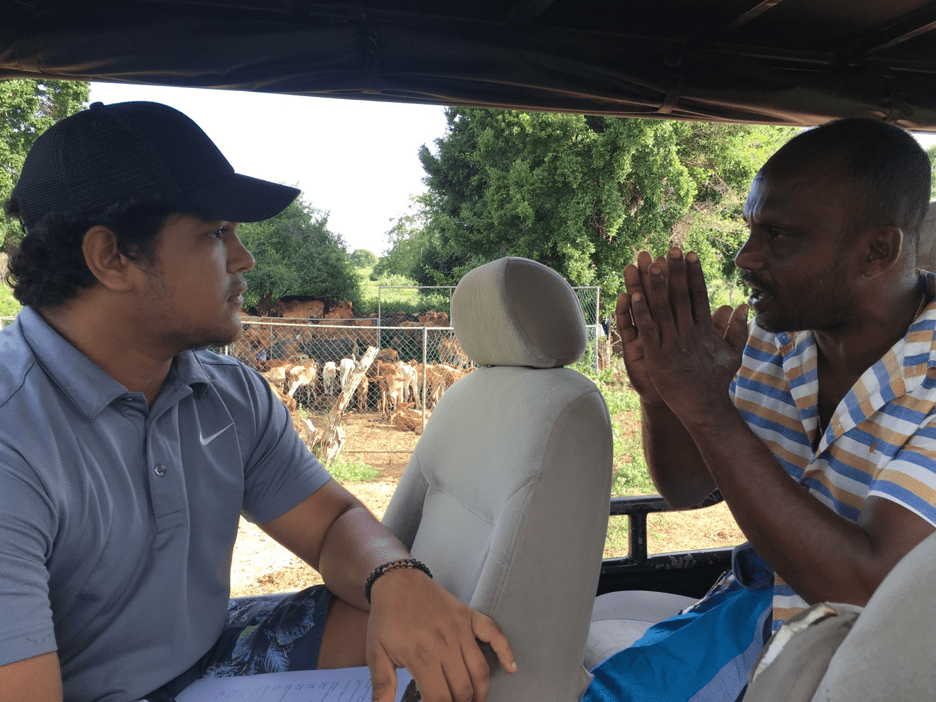

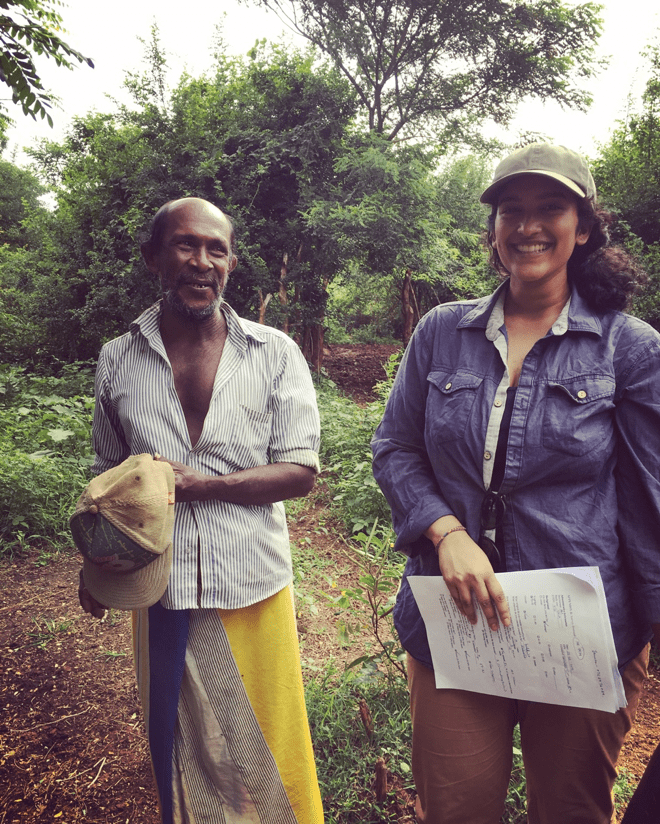

Social surveys being conducted with local cattle herders (right). In the background is a steel pen, that some herders in the area have been given in order to better protect their cattle from leopard depredation.

The results can be used to inform and make recommendations to local cattle herders and dairy cooperatives and guide researchers and policy-makers on practices needed to ensure stable leopard populations. However, this project is relevant beyond the confines of Sri Lanka’s small land area. Regardless of where conflict is taking place, be it on Vancouver Island or the Ruaha landscape in Tanzania, results and lessons learned from each context can help guide future research in coexisting with carnivores in increasingly shared landscapes. There are many tools and programs being used across the globe to try and mitigate conflict, from structural changes to cattle pens to the use of guard dogs to compensation schemes financed by the communities themselves.

Setting up camera traps requires many trials and adjustments, often using sticks to help angle the camera in the right direction.

Whether or not these options are feasible for the local Sri Lankan context will require this baseline work to be done, and an assessment of the affected community’s level of support towards these various options. After all, if communities aren’t supportive of a program, then there is little chance for its success!

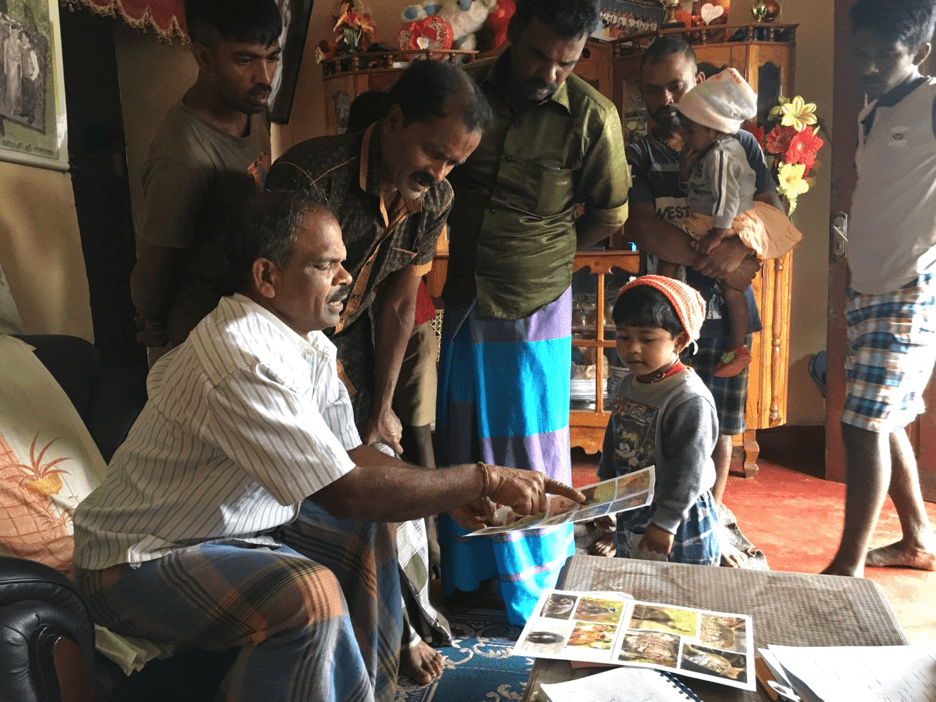

Sri Lankans are known for their friendliness and hospitality, and my experience echoed this. Many herders were very interested in this research, gave us a lot of detailed information and were keen that I come back to share the results – something I plan to do in my next field season!

Interviews being conducted in the Central Hills, where cattle owners often work on tea estates as well to earn extra income. In this photo they are identifying wildlife in the area.

A common way of keeping cattle in the Central Hills of Sri Lanka in the numerous tea estates. Cattle here aren’t being lost to leopards, however disease and miscarriages are the leading cause of their death.

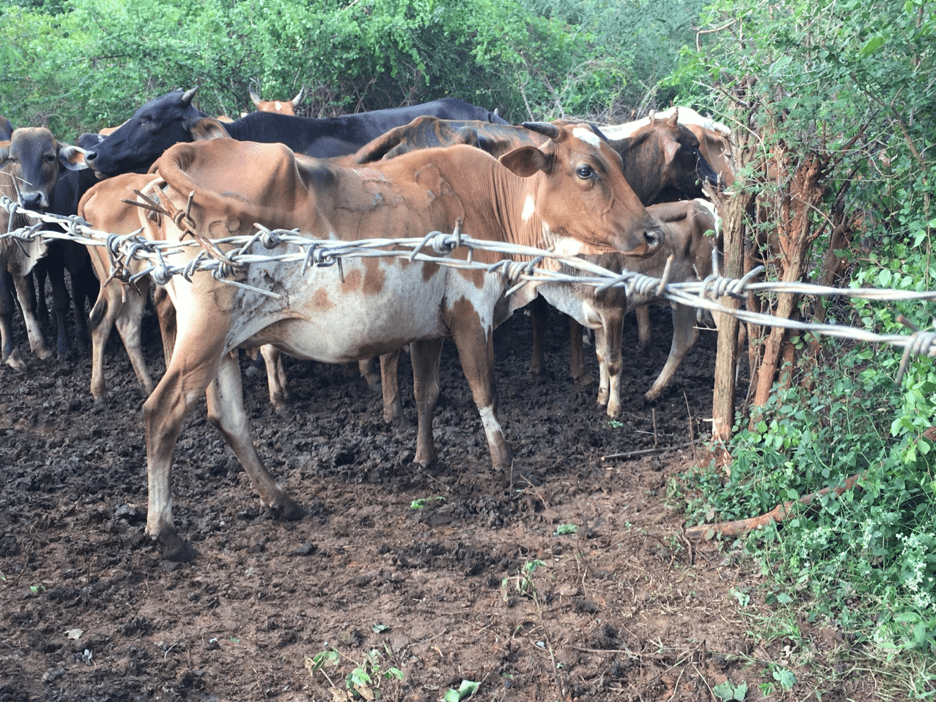

Cattle herders in the Yala region predominantly use this sort of ‘pen’ for their cattle, comprised of barbed wire and thorn bushes to deter leopards, but they act to mostly keep the cattle inside.

Some advice I can give after my time in Sri Lanka: Appreciate that no two sites are the same (even within a small region, within a small country) and lean on local participants and those with expertise for help navigating these complex nuances and attitudes. It takes years, even decades, to fully understand a system and its biological communities, but large carnivores simply do not have decades to spare!

The best part about using camera traps are the photos – elephants will always be amazing animals to look at, even though they’re not included in this research!

Crocodiles such as this one (Crocodylus palustris) are also a cause of cattle loss, particularly during grazing times where cattle are left free to roam around near watering holes.

Thank you to the Wilderness and Wildlife Conservation Trust, Cinnamon Wild, and the many other Sri Lankans who have aided and allowed me to carry out this research. I am extremely grateful for research funding from The Rufford Foundation, National Geographic, Greenville Zoo and IdeaWild to allow me to conduct this important research.

Blog: aishauduman.wordpress.com

Shop for a cause

Shop on amazon.com | amazon.co.uk