Víctor lays back in hiding, listening as a jaguar licks at the insides of a fresh sea turtle kill. The greedy slurping outpaces the pulse of the Caribbean surf rolling in just yards from his hideout. Trade winds push warm air off the waves. And lights, a mile distant, radiate upward from the small Mexican fishing village, Mahahual, muting the starry night sky overhead.

The Mayan jungle begins where the Caribbean Sea ends. Its canopy is home to tangles of black howler and spider monkeys, and its branches host a medley of sharp-dressed birds. The jungle below supports a revolving cast of characters ranging from tapir and caiman to coati and jaguar. Coastal jaguars have stalked out of the jungles each summer to hunt nesting sea turtles. As this particular jaguar laps at the egg yolks sliding out of the Loggerhead’s three-foot-long, torn carapace, Víctor rises from his hiding place and begins snapping photographs. The jaguar turns to eye him with an apex predator’s nonchalance, golden yolk dripping from its chin. It turns and vanishes into the shadows.

Every nesting season, jaguars leave the jungles to hunt nesting sea turtles. This young male was photographed shortly after eating the eggs from inside a fresh turtle kill. Photo by Víctor Rósales @vicwildphotography

“Education is the only thing that will change my community’s relationship to these animals, this ecosystem” Víctor says, scrolling through photos worthy of National Geographic stored haphazardly on his phone. The pictures help him teach classrooms of children about these animals, instilling both a regional pride and understanding he hopes will one day reduce illegal hunting in the region. While a young male jaguar like this might harvest fifteen to twenty sea turtles in a given season, it’s part of the ancient order Víctor protects. The pollution, habitat loss, and unsustainable harvesting, however, are not part of that order. And these are areas where Víctor works tirelessly to restore balance.

The path that led Víctor Adán Rósales Hernández to the beach that night, waiting to ambush the most powerful feline predator in the Americas, is as curious as the journey that led his family to Mexico. It all begins with an octopus. More precisely, an organization nicknamed El Pulpo, which is Spanish for octopus. The United Fruit Company earned its nickname because its tentacles wrapped all over Latin America. At its peak, the United Fruit Company owned 42% of land in Guatemala, the homeland of Víctor’s parents. When a democratically elected president threatened the company’s landholdings, the United Fruit Company lobbied the United States government to get involved. The CIA orchestrated a successful coup on June 17th, 1954. The country fell into civil war shortly after. The 36-year civil war in Guatemala pushed Víctor’s parents and thousands of families like his out of the western Mayan highlands in the late seventies. Víctor was born in a refugee camp in Belize before his family migrated north into Mexico.

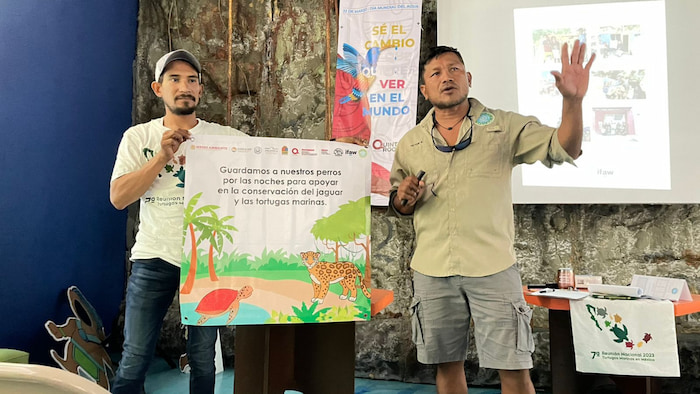

Víctor Rósales (right) is the founder of Aak Mahahual, a nonprofit dedicated to protecting Mahahual, Mexico’s sea turtle population. Photo provided by Víctor Rósales.

Life was not easy for the refugee family arriving in a new land with little economic opportunity. Relief came for Víctor when he joined the Mexican military. Order and routine replaced the pressing doubt and uncertainty of childhood poverty, and it gave him a secure foundation from which to build a life. Years later, with a family of his own in tow, Víctor settled in Mahahual. The Costa Maya Cruise Ship Port, christened in 2001, had recently opened the region to tourism. Summoning all his military discipline, Víctor studied English and biology, understanding that these were his path to accessing the types of opportunity the cruise port made possible. In time, Víctor began gathering his slice of the West’s largesse as he guided scuba divers intent on exploring the pristine coral and wildlife it attracts.

Víctor’s ecological awakening came when his scuba boat captain invited him to a sea turtle harvest. Had he been raised in Mahahual, harvesting a sea turtle might have felt nostalgic. Turtle is a traditional holiday dish for families across Mexico and much of the Caribbean. But with mounting global pressure, the Mexican government banned the harvest and trade of sea turtles in 1990. This slowed the harvest, but tradition doesn’t stop overnight. Even today, turtle meat is on the menu come Easter and Christmas. The locals here call the meat beef due to its red color. And there’s a significant amount of beef inside the three to five foot long shells. But the only thing Víctor could think of as the captain cut into the endangered sea turtle was the hypocrisy of butchering the same wildlife that supports the tourist economy of his community.

Víctor veers the car in sharp angles along a scarred and limestone-studded beach road. The headlights reflect back verdant spikes of thatch palm and spanish bayonet crushing in. The same geology that built the nearby Chacchoben ruins, now so violently shakes the car’s frame that the interior’s spackle of dust begins to jitter and coalesce into the low spots. “So I quit working with him. I started patrolling the beaches at night.”

It’s a penance. It’s an offering. It’s a mission that makes sense in a world that often does not. “I need to be on the beach at night when poachers are active. Nine until as late as one. If I come across a nesting green turtle later than midnight, I’ll usually just lay down next to it and sleep because they take sometimes three hours to dig their nests.”

His conservation efforts are now formalized as a nonprofit named Aak Mahahual, aak being the Mayan word for turtle. It’s a one-man, shoestring operation that’s piled on top of running his business, Mahahual Ecotours. The operational tempo is strenuous during turtle nesting season, but one he grew accustomed to in the military. He smiles and rubs a hand over his eyelids, not so young anymore. “I’m tired.” He shakes his head. “Always tired.”

We park on a side street near the Costa Maya Cruise Port entry and hike east into the jungle. It’s all black now, except for the red light reflecting back to us from our headlamps. At one point, Víctor crouches and points to a patch on the limestone path where a puma, one of six big cats calling the jungle home, had cleared the leaf debris and urinated. He presses a finger into the damp patch and raises it to his nose to verify. The tunnel eventually gives way to a palm grove on the beach, and we emerge just north of the massive cruise ship pier. It’s night, but light from the pier illuminates the swaying palm fronds fighting the trade winds. A single fisherman looks over his shoulder in our direction. And as we hike north along the coastline, the pier light fading at our backs, Víctor says, “Sometimes they wait there, the fishermen, to see whether or not we’re patrolling. If we don’t show up, they know they’re free to hunt.”

Not only for meat, but eggs. A single turtle egg, imbued with a perceived aphrodisiac quality due to the turtle’s reputation of marathon coitous, fetches up to twenty pesos on the local market—that’s roughly one U.S. dollar. In an area where monthly incomes average 150 to 225 U.S. dollars equivalent, selling a bucket of eggs amounts to a financial windfall. Such a feast and famine economic existence isn’t unusual for residents where the vagaries of tourism account for some 80% of economic activity.

As the lights from the pier disappear behind us, the coastline begins to feel more remote and wild. Our world shrinks to the confines of the paltry red glow of our headlamps. Víctor stops and points to the first nest of the season. He found it just two nights before. He has GPS coordinates and dates of every turtle nest in his region going back at least three years. This is manageable work because the numbers of turtles arriving each season are modest. On a night when both loggerhead and green turtles are laying, a busy night might involve seventeen turtle sightings. There are beaches where turtles arrive by the hundreds.

Down slope of us, between the nest and water, rests a wall of sargassum pushed into itself and mounded three feet high. This wall of floating seaweed extends fifty yards in either direction. Upslope, creeping grass, similar to what you might find on your lawn, chokes out once wide-open expanses of sand. Years of carbon deposits from decomposing sargassum have turned sand into soil. The tangle of roots make digging hard to impossible, forcing these sea turtles to dig nests in increasingly inhospitable sites too near the water line.

Sargassum is a relatively new invader of Caribbean beaches. It’s not only a problem for sea turtles, but tourism as well. The exact causes for these blooms isn’t fully understood, but it’s believed that nutrient runoff from the Amazon, the Mississippi, and shifting deep sea currents carrying nutrient-dense waters upward in the water column surpassed a critical nutrient threshold and caused sargassum populations to seasonally explode. Carried by currents and wind, the noxious, rotting algae fouls the once idyllic white sand beaches across the Caribbean. Though the sargassum here is a problem due to its ahistorical volumes, the presence of some sargassum is vital to the life cycle of several species, including baby sea turtles that rely on it for protective cover and the bite-sized sea life it attracts.

Sargassum is a floating seaweed carried to Yucatán’s beaches by ocean currents and the trade winds. Its presence poses a challenge to both nesting and baby sea turtles. Photo by Víctor Rósales @vicwildphotography

The trade winds push a wave up and over the mounded Sargassum as Víctor scans the water line for turtles. I watch as a lone child’s Croc, the obnoxious but undeniably utilitarian foam shoe, poetically bobs in the surf. Plastic water caps, bottles, utensils, facemasks, jugs, fishing ropes and netting litter the seaweed and pile in obscene quantities across the beach. The volume of plastic debris is staggering. From our vantage, the single-use plastic debate isn’t some theoretical economic exercise or culture wars talking point. It’s a crisis.

This year alone, Víctor has organized and hosted several beach cleanups at nesting sites north of this one. That’s where we first met. I, a nameless member in a loose cadre of international conservation-minded travelers. He, a gregarious commanding general, gathering trash and spreading enthusiasm for the mission at hand–as natural leaders naturally do. Our ragtag group of volunteers, with native French speakers speaking English to English speakers speaking Spanish to Spanish speakers speaking English and so on, removed literal tons of plastic waste from the nesting grounds. This beach, the one whose waves lap at my feet, is too far removed from roads for such humble clean up efforts. So we kick the plastic aside to find solid purchase as we walk the sloping sands.

Despite the global nature of the Sargassum grasses and plastics choking this beach, there’s good reason for lone players to be out here working the local beat. Since before language, sea turtles made landfall on beaches just like this all across coastal China. But over time and beach by beach, the turtles stopped arriving. Habitat destruction, over-harvesting, and suffocation in fishing nets wiped out many of these regional populations entirely.

What’s lost in the ecosystem when these turtles disappear is hard to quantify. “We were not studying the structure of marine ecosystems before the overexploitation of sea turtles,” Dr. Elizabeth Whitman, a biologist at Florida International University, explains. It is clear that these species do play a role in shaping the ecosystem. “Green turtles structure ecosystems by consuming seagrass,” Dr. Whitman continues, “habitat use and movement patterns of all other species that use seagrasses and all trophic levels above them are impacted by changes in seagrass distributions.” If ecosystem services provided by turtles were to suddenly stop, the resulting imbalance would certainly be felt–and likely in some unexpected ways.

Plastic waste in the ocean can bind and suffocate sea turtles. Photo provided by Víctor Rósales @vicwildphotography

Extinction is a fate that Víctor can’t bear for the regional loggerhead and green sea turtle populations within his area of responsibility. Based on his data, loggerhead nest counts in his region are going down. Loggerheads spend most of their lives foraging the open ocean. Their range is extensive, nesting on every continent but Antartica. However, this vast range does not imply a thriving population. They’ve been classified as either a threatened or endangered species (depending on the region) since the late seventies. Weighing up to three hundred pounds and capable of crushing a conch shell in their beak, these carnivores live a long life and don’t reach sexual maturity until they’re between seventeen and thirty-five years old. That’s when the females return to the beach of their birth to lay eggs, sometimes traveling thousands of miles to get back home.

In the Yucatán, May brings with it the early layers. Throughout the six month nesting season, they’ll lay between two and five nests. Of all the eggs buried in the sands across the region, only one in two thousand will survive to sexual maturity. If only one in two thousand humans today were alive, the global population would be around four million.

Víctor’s self-assigned conservation beat spans 65-kilometers from where we stand just outside Mahahual north to Pulticub. There are four nesting beaches in this stretch, and he can only patrol one a night. Unfortunately, there is little to no additional support from the government. “Mexico has bigger problems than protecting sea turtles.” Victor explains with a shrug. And the Sian Kaʼan Biosphere Reserve, a UNESCO World Heritage Site located just to the north of his territory, attracts the bulk of conservation interest into the region. We continue up the beach, stopping every twenty meters to scan for incoming turtles. He points to a green turtle nest from the previous season. It looks like a bathtub.

The green turtles arrive later than the loggerheads, and both share the same nesting beaches, with peak nesting activity in June and July. These turtles are herbivores and named after the resulting green hue found in their fat. They are larger than the loggerheads, coming in at five feet in length and over four hundred pounds on average. Though, the largest recorded weighed an astonishing 871 pounds. Like the loggerhead, the green turtles have multiple nests in a season. They average between eighty-five and two hundred eggs per nest.

This bounty of eggs brings out more than just illegal gatherers. A parade of loose dogs, led by their noses and compelled by their stomachs, take to the beaches every night to dig up these nests. With jaguars on the prowl for turtle meat, conflict is inevitable. Dogs die and the locals fear for their children and themselves. So they shoot these endangered cats on sight. To ease this tension, Víctor secured funding through the International Fund for Animal Welfare to finance the construction of over 145 steel dog cages along his stretch of coast. By penning up dogs at night and educating locals about jaguar habits during turtle season, Victor hopes to change the community’s sentiment and conserve the remaining jaguar population.

Aak Mahahual, in partnership with the International Fund for Animal Welfare, built 145 dog cages to help reduce conflict between jaguars and local dogs–saving the lives of both species. Photo provided by Víctor Rósales.

Víctor has had his run-ins with jaguars on the beach. When asked if he’s worried about getting attacked, he laughs. “It’s the poachers that I worry about.” And this isn’t an unwarranted fear. Mexico is one of the deadliest countries in the world to be an environmental activist. According to the watchdog group, Global Witness, more than 1,700 activists have been murdered in Mexico in the past decade. That’s nearly one conservationist murdered every two days. Any activist getting in the way of industry like wildlife trafficking, poaching, logging, or mining is a target. In the midst of a mounting climate crisis and the sixth major extinction, there’s a sad irony at play when environmental defenders are murdered by those forces driving these twin crises. It’s like a body rejecting a necessary immune response.

Víctor once stopped two grown men collecting turtle eggs in five-gallon pails. He approached amiably and explained the importance of turtles in the ecosystem and tourist economy. The men dropped the pails and walked away. Víctor reburied the eggs as he’d been taught by agents from the National Commission of Natural Protected Areas, an institution of the Mexican government whose primary function is to ensure the conservation of Mexico’s natural heritage. Two days later, a regional poaching ring leader boxed Víctor’s car in at the local gas station and held a pistol to his chest: “You stop my crew again, and I’ll fucking kill you.” Or something to that effect. It was all said in Spanish, and I wasn’t there. But Víctor’s retelling got the point across: If he got in the way of the money again, he’d be dead.

Travellers and locals volunteer with Aak Mahahual to patrol beaches during the sea turtle nesting season. Their presence on the beaches is often enough to deter illegal hunting and egg harvesting. Photo by Víctor Rósales @vicwildphotography

So now he won’t patrol the beaches alone. He relies on the company of volunteers to establish safety in numbers. Which is why I’m here, finding a seat for myself in the sand. Nature works at its own pace. We don’t wait for the turtles to arrive, rather we make ourselves available if they need us. There’s time for silence now, to absorb in the wild Caribbean and the jungle at our backs. But then a question arises as I absorb the immense forces arrayed against the sea turtles and let fatalism creep in: “Do you have hope?” I ask. “It all seems too big, doesn’t it?”

Víctor turns to me. From the look on his face, it’s a question he’s asked himself before. Will his sacrifice, one so taxing on him and his family, make an impact? “It’s true,” he responds. “There are global issues here that I cannot fix alone. But there are local issues where I can make an impact. And as long as there is something I can do to help, I will.” In an age where cynicism and fatalism too often rob us of our personal agency, Víctor’s sentiment seems to hold within it the solution we’ve all been looking for.