The walls are closing in on one of our most important predators in the United States. Pushed to find refuge in their shrinking home, mountain lions (Puma concolor) are struggling to find a place among a species that has lost sight of their role within the natural world. Humans have become one of the deadliest forces for these wild species in modern society, inflaming our continual drive to build in the name of “progress,” which leads to detrimental effects on the wild places that provide so much for our lives. We creep our way through untouched landscapes and find ways to take up arms against wildlife as they try to adjust. What can we expect from this type of change? What have we already been coping with?

Human encroachment is leading to the loss of habitat available for our wild neighbors to create suitable home ranges and survive. We build homes in spacious and beautiful places that were considered this way because they were untouched. However, we now flock there with our homes and vacation properties, causing further development to follow. All these scars on the land push wildlife to disperse from important habitats for their survival, but there is only so far they can go when we keep closing in. Looking at the numbers, we can see a growing issue throughout the world. In the United States alone, our population has increased by 26.2 million people from 2010 to the present (U.S. Census Bureau quickfacts: United States). The influx of humans on the landscape means we need to create places for these people to live. Looking in my own backyard, the figures are startling. From 2001 to 2021, landscape data from the Multi-Resolution Landscape Characteristics Consortium shows a troubling trend of losing natural lands in San Diego County. Over the last 20 years, we have seen a 5.54% increase in total developed areas, a 9.05% increase in impervious surface area, and a 41.69% decrease in forested areas (MRLC NLCD Eva Tool). These staggering numbers are the reason you may be hearing about habitat fragmentation, a phenomenon caused by over-development that has negative consequences for wildlife fighting for survival in a human-dominated world.

To understand the full effects that altering the health of mountain lions can have on the ecosystems they reside in, we must first understand the roles that these species play. As a keystone species, the mountain lion regulates populations of other species that, left unchecked, can lead to disruption of the landscape. Prey species like the mule deer (Odocoileus hemionus) are herbivores and graze on different plants throughout their range. If mule deer were to lose this top predator, there could be huge consequences for the abundance of their forage species and further effects reaching throughout the environmental community (categories of keystone species, see Appendix I). These connected consequences are known as a trophic cascade and can cause entire ecosystems to disappear. A good example of this happening is with gray wolves (Canis lupus) in the Greater Yellowstone Area. By the 1920s, there were no wolves left in Yellowstone after the immense hunting pressures of a bounty system set for predator control (Beschta and Ripple, 2021). Getting rid of the wolves was the end goal, and mountain lions came under fire as well, although the more secretive behavior of the large felid allowed it to sustain more of the onslaught from the bounty. However, the lack of understanding of natural processes led to adverse effects for all life in the region. As the wolf’s primary prey, the elk (Cervus canadensis), went unregulated by their biggest predator and took over the landscape, there was irreversible damage done to the park from trampling and overgrazing that can still be seen in Yellowstone today (Beschta and Ripple, 2021). These issues can be repeated in any ecosystem when a keystone species is removed, making it important to focus on them and ensure their habitats are protected.

Unfortunately, we are struggling to protect these important home ranges for the keystone species we all rely on. Many factors contribute to this shortcoming and cause more stress on everything living within the region, whether it is outdated management techniques, lack of funding, or lack of support from a political standpoint. All these factors and more contribute to an ongoing and increasingly stressful environment for the mountain lion to continue to survive in. The main course of action humans take to interfere with the natural state of wildlife is to develop their habitats. The population boom and the need for more infrastructure to support this growth have led to greater landscape changes across the natural range of the mountain lion. In California, the land is being parceled out in portions ranging from 1-40 acres at a time (Human/Wildlife Interactions in California: Mountain Lion Depredation, Public Safety, and Animal Welfare - Amendment to Department Bulletin 2013-02). As these areas of developed lands grow and start connecting with other parcels, it causes habitat fragmentation.

Learning the behaviors of different species and what they need in a habitat to sustain healthy populations gives us deeper insight into the full extent of consequences habitat fragmentation has on them. Individuals of a cougar population can be grouped into four categories: adult males, adult females, dependent young, and subadults or transients (Negri et al., CH. 5 Cougar Population Dynamics). Male mountain lions are known to have larger home ranges than females. Males establish a territory that encompasses the same area as multiple females’ home ranges to secure their reproductive success in the area (Negri et al., CH. 5 Cougar Population Dynamics). Males are also territorial by nature and will defend their home range aggressively from other male competitors or young that were not sired by them. This territoriality is believed to play a role in the natural regulation of populations, but when mixed with humans disturbing the land, other issues arise with these population dynamics. Habitat loss and fragmentation are one of the greatest risks to mountain lions and many other species on our landscapes. It occurs when large areas of suitable habitat are divided and developed for various reasons such as industrial, residential, roadways, and more. By adding these aspects to the landscape, processes are interrupted that affect mountain lions in intricate ways. Intraspecific killings, where one species kills another individual of the same species, is a major component of the mortality rate of this species. Because the fragmentation of land cuts them off from obtaining their own independent ranges in other habitats, it worsens the issue of mountain lions killing mountain lions. Additionally, we are also causing increased risk of mortality to mountain lions from road development alone. Habitat fragmentation leads to increased vehicle collision deaths of these large felids due to the expanding maze of highways (Lions in the Santa Monica Mountains). The dangers here are not only to the mountain lion but also to every single individual who gets behind the wheel and travels these highways. A collision with one of these animals could be deadly to both parties and other motorists on the highway. It could also be avoided completely. The use of wildlife crossings allows these animals to move past our anthropogenic boundaries and reestablish habitat connectivity.

Facing the effects of shrinking habitats, it is important for humans as a collective to understand and help implement practices to support mountain lion dispersal. They rely on it to maintain healthy genetic flow, reestablish historic range, and avoid intraspecific mortality. Typically, dispersal is witnessed in young subadult males; however, about 50% of female mountain lions will also disperse while the remainder stay philopatric to their natal areas (Hornocker et al., CH. 8: Behavior and Social Organization of a Solitary Carnivore). The act of dispersing from the natal range of a mountain lion occurs around 14 to 16 months. As they learn all the necessary skills of survival from their mother, individuals that disperse will set out on a daunting journey. They will have to navigate through territories of older territorial male lions that these young subadults are not equipped to battle and find passage through the sprawl of human development. Roadways, residential communities, and rural farms all pose challenging obstacles for these newly independent cats to avoid. Some of these young mountain lions have been recorded using small transient home ranges as they move, thought to be for prey resources and for avoiding territorial males in the area (Beier 1995; Logan and Sweanor 2001). This is where we see the importance of maintaining the connectivity of their habitat. The less room they have access to, the deeper they get pushed into a corner they cannot escape.

Mountain lions need space for many reasons, including their large home ranges extending up to 150 square miles, to avoid competition for mates, and to secure a sustainable prey resource. They also depend on being able to reach other populations to maintain their genetic diversity. The Florida panther (Puma concolor coryi) is a subspecies of Puma concolor, the mountain lion, and is one of the most endangered large mammals in the world. The cause of this was habitat fragmentation. A once connected population from western Louisiana all the way to eastern Florida and potentially further north was cut off and began to dwindle in numbers. The inbreeding caused by geographic isolation and habitat loss led to the loss of their genetic variability (Florida panther - army). This shows us the importance of supporting a natural and suitable habitat for the mountain lion. As we continue to divide the land into more sections of altered landscape across the entire range of this species, we are likely to see the same damaging effects as the Florida panther occurring in other areas. Humans keep closing in and tightening their grip around the elusive apex predator, and the list of consequences reaches even further, directly affecting those who live in or frequently visit the places mountain lions roam.

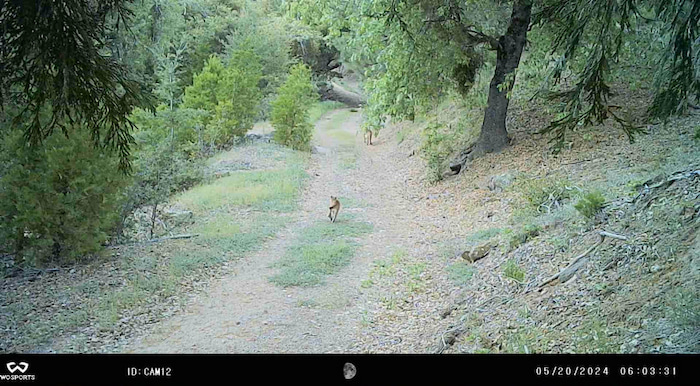

More than half of California is suitable mountain lion habitat, and coupled with behavior that is extremely solitary, elusive, and has a

preference for rugged and steep terrain, it’s no surprise that they are very rarely seen. However, that is beginning to change as people find ways to encroach on lion habitat. The National Park Service began research in the Santa Monica Mountains National Recreation Area in 2002 to help understand the impacts of urbanization and fragmentation on mountain lions and their habitat. When the study first began, the only resident male mountain lion was P1. He fathered all the kittens born in the area until he was killed by a vehicle in 2012. The lack of a mature resident male in the area opened the door for mountain lions from outside the Santa Monica Mountains to come in. This created an increased risk of intraspecific killing within the region, where new males killed kittens sired by P1. The park saw a decrease in population with an increased mortality rate as dispersing young lions moved in and out of the mountains through high-traffic roadways . P22 was one of these young dispersing lions that made it to the Santa Monica Mountains but ultimately found himself in Griffith Park. It is believed he crossed both the 405 and the 101 freeways to get there . This feat is astounding when you think about how much development is within this range, and it highlights the necessity of better wildlife connectivity measures to provide safer and more suitable habitats for this species. When we fail to address issues such as habitat fragmentation, mountain lions will have no choice but to disperse wherever they can find space. This is why we are seeing an increase in lion presence in urban settings.

Many people have the privilege of living next to wild lands and traveling through untouched mountain ranges, but with that comes the need to respect that these areas are also home to wildlife that has very specific needs to continue their way of life. Livestock depredation is one of the leading reasons that mountain lions are being killed (Human/Wildlife Interactions in California: Mountain Lion Depredation, Public Safety, and Animal Welfare - Amendment to Department Bulletin 2013-02). We remove them from the land by developing it and pushing them to find alternative places to live. When that is no longer possible, they will have to resort to their basic needs, which is to find food and water and to protect themselves and their young. Domestic animals become targets for the apex predator because we have left them no other choice. These lions have no space for prey availability and are becoming more desperate. They become threatened, and that leads to more public safety issues. By having little understanding of the life history and behaviors of mountain lions, we cause unnecessary harm to them by not recognizing that they need space to survive.

When looking at these negative impacts from human development, we can gain more knowledge of the keystone species and how they affect us as individuals in the places we all love. Each state has different legislation on how they protect mountain lions. For example, in California, they are specially protected species under the California Wildlife Protection Act (Human/Wildlife Interactions in California: Mountain Lion Depredation, Public Safety, and Animal Welfare - Amendment to Department Bulletin 2013-02). This status means that mountain lions cannot be hunted recreationally and allows some protections to help limit killing mountain lions. They are still under threat from a variety of other means and have no protection against these. From 2000 to 2020, 1,951 mountain lions were killed in the state of California alone for depredation and public safety purposes (Human/Wildlife Interactions in California: Mountain Lion Depredation, Public Safety, and Animal Welfare - Amendment to Department Bulletin 2013-02). This may seem like a small number over 20 years, but with all other threats like vehicle strikes, it is unsustainable for the populations that we have in California. Colorado, on the other hand, allows sport hunting, and this can lead to an imbalance in sex and age structures within the population of cougars that they have (Hornocker et al., CH. 9: Cougar Management). It has also been observed that older, more established male lions are likely to be targets of these hunts because of their size, which is viewed as a bigger prize (Hornocker et al., CH. 9: Cougar Management). Losing these resident males could cause issues for the dynamics of dispersing subadults and increased intraspecific mortality for the region. When you remove apex predators, the ecosystem is also disrupted as the prey animals they would hunt go unregulated. Without hunting pressure, these animals’ populations will boom, and food availability will become an issue for everything within the area. One study found that due to sport hunting pressures in the state of Colorado, the number of cougars born and surviving within the state had drastically decreased. It was also concluded that the populations of the species would not be able to sustain themselves under current management strategies (Hornocker et al., CH. 9: Cougar Management). Each state should look into other methods of coexistence and education, like the mountain lion policies found in California, to create more protections for the species. By doing this, they will better understand these species that have a role in their environments. This knowledge can lead to us avoiding conflicts such as human-wildlife conflict issues while recreating or hunting ungulates in mountain lion habitats. This knowledge would help us understand how to avoid negative situations for both humans and mountain lions.

Implementing conservation efforts that consider both species’ needs and societal benefits is crucial for us to continue to grow. Conservation measures for the mountain lion do not stop at simply maintaining populations. It goes further by understanding their behavioral traits and their life histories that allow them to sustain their way of living and how that relates to us. When we support our environments and wild areas, we are supporting ourselves. The fragmentation of landscapes for wildlife, especially the mountain lion, has devastating impacts on the ability of these species to thrive in their historic and native ranges. Coupled with our increasing development, vehicle collisions, public safety issues, and lack of understanding of the natural world, it is easy to see that we need to act now. By working with policymakers, wildlife agencies, and the public, we can bring these important ecosystems back and find ways to coexist with our elusive apex predator, the mountain lion.

Main image by Adriaan Buys