Whether listening to a local explaining how he propped his ladder up against the wall of the nature reserve to have a view in because he enjoyed it or thatch grass being gathered on a high hill with an unbeatable view of a herd of zebras, their backdrop being the blue Indian ocean and one of many rivers which meander seawards’; or watching rhinos in the morning, and in the afternoon hearing how community members so value these giants that they report poachers … all point towards communities inextricably linked to the protected areas which they live next door to.

With a long-term passion concerning the connection between humans and their environment and the desire to provide practical solutions to enable these connections to be positive, my research took root in three vibrant South African communities and the special nature reserves they bordered. Nearby the capital city of Pretoria, the semi-urban Kekana Gardens community borders the big-five Dinokeng Game Reserve, a unique partnership between the provincial government and private landowners who have dropped their fences. Moving to the rolling hills which flank the Wild Coast of the Eastern Cape, the Khanyayo people are the community living closest to the magnificent Mkhambathi Nature Reserve, a provincial reserve in a biodiversity hotspot and known for its grazing herbivores, huge rock pools and multiple waterfalls (one cascading directly into the sea). Continuing to KwaZulu Natal, the Mnqobokazi community borders Phinda Private Game Reserve, a big-five sanctuary containing seven distinct habitats. Working with these three very different reserves deepened the perspectives, and using a mix of qualitative research methods enabled different voices to be heard. What was I looking for? An understanding of the perceptions of both the park stakeholders and locals regarding people-park relationships.

Khanyayo community, Eastern Cape (Closest village to Mkhambathi Nature Reserve)

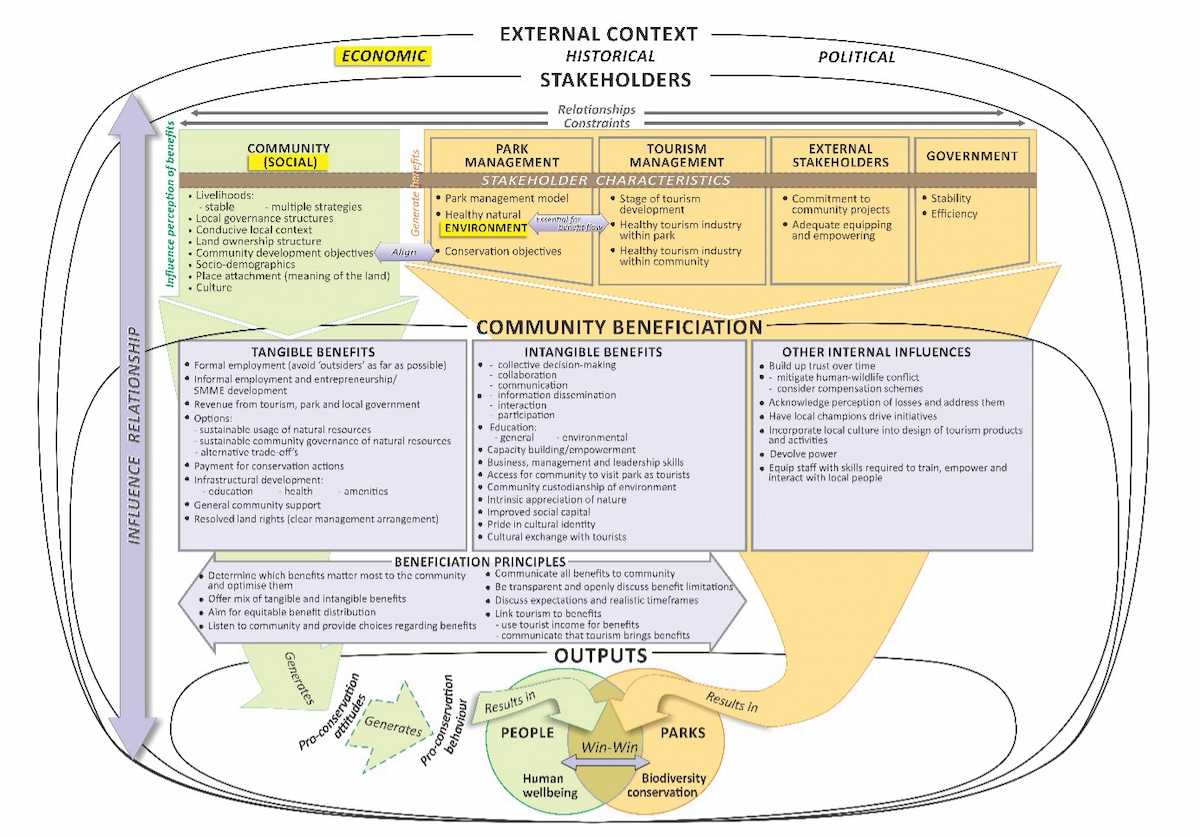

What was interesting was the differences between these perceptions. Park staff and local communities often differ on which benefits matter most to the communities and on what the costs of bordering a protected area are considered to be. Understanding these differences builds relationships, but first, you have to know what each group thinks! Based on the findings from the three case studies, I first produced the model on the influences on attitudes of local communities towards protected areas, which outlines the main benefits and losses perceived due to living around a protected area, what facilitates or detracts from positive attitudes towards the park, and practical solutions on how to improve positive attitudes towards the park. The model comes with a set of practical recommendations for both communities and protected area management. It’s important to acknowledge the roles and responsibilities of the community too in improving people-park relationships.

Mnqobokazi community, KwaZulu Natal (bordering Phinda Private Game Reserve)

The second step was to combine this model with what other researchers have found to develop a more holistic "People Parks Win-Win framework". This represents the multi-dimensional influences on people-park relationships. It’s not a rigid tool but can be customised to different settings. The framework sets out the different stakeholders involved and how their different situations influence relationships, the range of benefits possible, and key beneficiation principles. Let’s look at some of these principles:

Getting the mix right: Parks often focus on tangible benefits such as employment – very important, but limited. With parks in Africa facing budget and staff limitations, its critical to know that communities rate intangible benefits highly, sometimes above tangibles. So benefits such as environmental education, being able to visit the reserve, information about the reserve and interaction with park staff are also highly valued and improve positivity. On the flip side, acknowledging costs perceived by communities and addressing these can also improve relationships.

What matters most? Find out which benefits matter most to communities and focus on these. For example, a vital intangible benefit identified by communities (but sometimes not recognised by parks) is that communities want to be custodians of the park and want to have responsibilities to protect it. Locals often show a deep appreciation of nature and the need to conserve it. Once this is known, it can be nurtured – a clear win-win!

Do communities know? Generally, park staff listed more benefits than communities did. So it's important to get this information out there with clear and regular communication.

Being realistic: Be transparent, discuss expectations and realistic timeframes, and openly discuss the limitations of a park's offerings.

In our special and vibrant African context, the dual achievement of community well-being and conservation is essential from an ethical perspective for protected areas to survive and thrive. An integrated approach to conservation planning that highlights social equity, trust, respect, and optimal benefit-sharing is needed. This can lead to pro-conservation attitudes, sometimes leading to behaviour that enhances conservation. Win-wins are complex, but by understanding the perceptions of communities and park staff, the right tools can be developed to further the roadmap towards long-term sustainability – for both people and parks.

Queiros, D.R. 2022. People Parks Win-Win Framework: Integrating components that can influence people-parks relationships. KOEDOE, 64(1):1-16. Available at: https://koedoe.co.za/index.php/koedoe/article/view/1723