A New Destination, A New Challenge — A Rocky Mountain Horror Show

As we drove out of Calgary, the Rockies reared from the prairies, with their thickly forested lower flanks rising to razor-sharp ridges and snow-capped spires. While they don’t contain Canada’s high point, Logan (5959m), they do constitute its defining range, stretching 1500km south to north. The wife and I had planned to climb the highest Rocky, Robson (3954m), but wildfires further north blocked our way. So, we selected the tallest in the southern section, Assiniboine (3618m), which was easier to get to, if harder to spell.

Looking to climb Assiniboine yourself? Check out our Helpful Tips at the end for advice on timing, routes, and logistics!

Naming Mount Assiniboine: The Matterhorn of the Rockies

It was so-named in 1885 by surveyor George Dawson who, on spotting this distinctive spire, was reminded of the teepees of the Assiniboine tribe. It could have been worse with other local landmarks, including Shaganappi Hill and Lake Minnewanka. Thankfully, Assiniboine was quickly nicknamed ‘the Matterhorn of the Rockies’, and from certain aspects does resemble the iconic Swiss alp.

While awaiting a freight train to rumble over a crossing, I gave up counting after 50 wagons. To be fair, Canadian Pacific Railway (CPR) opened up the Rockies to tourists like us, back in the 1880s, as part of the so-called ‘National Dream’ to unite the fledgling nation. CPR also built accommodation in the interior, with its boss pragmatically declaring, ‘Since we can’t export the scenery, we’ll import the tourists’.

In 1901, CPR sponsored a visit by Edward Whymper, the celebrated English mountaineer who’d conquered the Swiss Matterhorn in 1865. CPR was banking on Whymper popularising the region by also bagging Assiniboine, which had rebuffed four attempts. When he arrived in the Rockies, 61-year-old Whymper was somewhat past his prime, prickly, grumpy and drinking heavily – and Fiona delighted in pointing out the similarities. But whereas Whymper had brought four guides from Switzerland, I’d sourced one locally. David Lussier had recently summited Logan for the fifth time, which seemed satisfactory credentials, particularly when he turned up with whisky and beer.

More by Matthew

Riding to Assiniboine Lodge

For early expeditions, reaching Assiniboine’s base required a torrid bushwack. Some progress is for the better and at the Mount Shark trailhead we clambered aboard a chopper, predominantly shuttling well-heeled tourists to Assiniboine Lodge, 5km north of the peak. Though the flight only lasted 10 minutes, the views were intense; soaring above Spray Lake and up Bryant Creek, then skimming over Assiniboine Pass, with our rotors almost brushing the cliffs.

At 2200m and only accessible by foot, skis, horseback or helicopter, Assiniboine Lodge boasts both rich clientele and history. Trespassing on the lodge’s veranda, we looked out across meadows of magenta fireweed and turquoise Lake Magog, to the sharply sculpted obelisk of Mount Assiniboine. That this vista doesn’t adorn chocolate box covers is presumably because most Canadian chocolate tastes like wax. Trying to ignore lunchtime aromas emanating from the kitchen, we shouldered packs and set off.

A Crawl along the Gmoser Highway and Arrival at Hind Hut

After skirting Lake Magog’s righthand shore, we took the off-ramp for the Hind Hut via the Gmoser Highway, with Gmoser referencing a Canadian ski-mountaineer, and ‘Highway’ presumably a joke. This so-called highway comprised a series of thin, crumbling ledges, vaguely connected by greasy, crumbling scrambles, above an increasingly solid drop. I would have found it challenging, never mind with clumpy mountaineering boots and a skyscraper pack. As I crawled on all fours, David offered tips on footwork, hand placement and posture, and seemed genuinely amazed by my incompetence.

After five testy hours we reached the Hind Hut, set on a col at 2700m, beneath Assiniboine’s North Face. This austere Nissan hut could have been airlifted straight from an army barracks, and two tall cairns nearby had the cheer of memorials. We’d no sooner crossed the threshold than the sky blackened, thunder growled and a lightning bolt struck the mountain.

A Prolonged Visit to the Hind Hut

We spent the next two days ensconced in the hut, listening to rain or snow. A single room with space supposedly for ten guests, we fortunately had it to ourselves, bar an opportunistic rat. Stocked with sleeping pads, cooking utensils and a gas stove, it was actually quite homely, at least compared to camping. The only inconveniences were the outside toilet involving a 200m dash, and the fresh water source double that. Nonetheless, despite our prolonged captivity and personal foibles, we remained on affable terms.

Conversely, Whymper’s relationship with his Swiss guides deteriorated from the off. On the long journey over from Europe, the class conscious Whymper travelled first class, while his guides went steerage. Then, once out in the hills, Whymper treated them as skivvies, dining separately, with his daily fare including a quart of whisky and six pints of beer. The brewing disharmony culminated in fisticuffs between Whymper and one of the guides, who all went on strike and drew up a charter setting out their rights. Thereafter, the quintet managed a few things, but avoided testing their teamwork on Assiniboine.

Each evening at 6pm, we received a weather forecast from the lodge by radio. And each morning at 4am, David dutifully stuck his head outside to check it was as bad as predicted. While I’d have happily curled up in my sleeping bag, he insisted on spotting sucker holes in which to venture out. The first day, we stomped up Mount Strom, a 3022m hump behind the hut. And the second, we cramponed around beneath Assiniboine’s Southwest Face, the route of the first ascent.

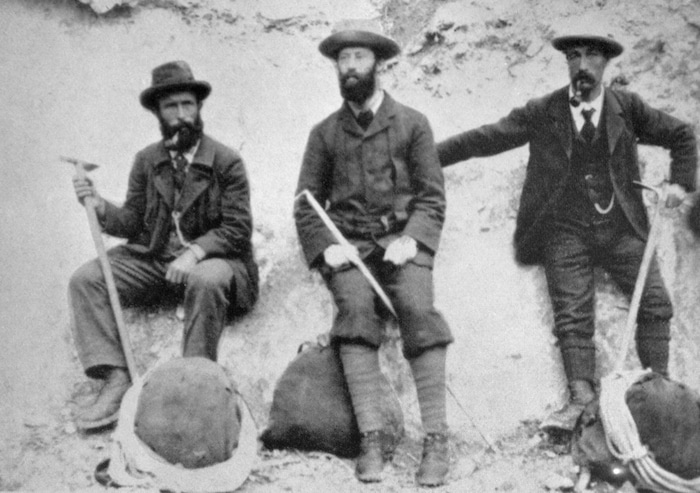

Assiniboine first ascent team L-R Hasler, Outram and Bohren (Glenbow Museum, Calgary)

The Conquest of Mount Assiniboine

In August 1901, Whymper’s fractious party bumped into James Outram, a 36-year-old English vicar visiting the Rockies to recover from corporate burn-out, having found his job too stressful. A competitive man of the cloth, Outram joined Whymper’s team for a few outings. Then, on hearing of yet another failed attempt, he raced south with two Swiss guides – Christian Bohren and Christian Häsler - plus two local horsemen, making camp beneath Assiniboine’s Southwest Face. On their first attempt, the trio got disorientated in dense cloud and mistakenly climbed a 3400m-pimple on the southwest ridge, now named Lunette Peak. But they tried again the following day and reached the correct summit, then the highest tagged in Canada. Not content, Outram insisted on descending via the North Ridge, thus traversing the mountain. After 13½ hours, they returned to their camp and a violin serenade by one of their horsemen.

The Proverbial Now or Never

By our third day, the weather had marginally improved, whereas the forecast thereafter had worsened. This was our window, the proverbial now or never. We left the hut at 5am, tottering by headlamp across a field of marbles. As we were quickly discovering, Assiniboine is best admired from a distance, and up close is a big pile of choss. We stumbled our way up to the North Ridge, which Outram’s party had descended, but is now considered the standard route up. Initially, it was marked with cairns and moderately angled. And when the sun appeared and we emerged above the clouds, I even caught myself thinking we’d make it and might be down for lunch. But then we hit the snowline, and cairns and holds disappeared, making even simple moves awkward and potentially calamitous.

We laboured up alternating scree slopes and rock bands, which were progressively more difficult and darker in hue. On reaching the Red Band, after three hours, we were shin deep in snow, wearing crampons, and under halfway. And at the Grey Band, a couple of hours later, I told Fiona our climb was surely done - but she ludicrously claimed to be enjoying it and David blithely carried on, swimming up several unprotectable pitches of powder. With the clouds below having evaporated, it was increasingly difficult to ignore the giddy exposure on both sides of the slender ridge.

Though our goal was visible, it wasn’t getting discernibly closer, and we had a strict turnaround time of 1pm. As the gradient eased, we broke into a jog, reaching the top with five minutes to spare. The summit was surprisingly spacious, though we gingerly skirted a lipped cornice overhanging the East Face, through which unsuspecting climbers have plunged to their deaths. To be honest, I didn’t appreciate the views, knowing it would take as long to get down.

Only Halfway There

With only four bolted rappels, the descent predominantly required downclimbing. And while we didn’t want to spend the night out, nor did we want to emulate Whymper’s Matterhorn descent, when one of his seven-man party slipped, pulling three more off to their deaths. By the time we reached the sanctuary of the col, the seat of my Gore-Tex pants was in shreds. And when we reached the Hind Hut at 9pm, just as the last daylight leeched away, there was no violin serenade. Coincidentally, Fiona and I had climbed the Swiss Matterhorn 32 years earlier to the day, on our honeymoon, in similarly trying conditions – which probably says something about our relationship, though I’m not sure what.

Early the next morning, we packed and left, spurred on by an incoming storm. Descending the Gmoser Highway as quickly as we dared, we reached the lodge just as the first raindrops landed. We’d hoped for a salubrious night there and a flight out the following morning, but they had no room for three haggard climbers. Instead, we had to march 25km to the trailhead, in drenching rain, through Grizzly terrain.

Getting Out

At least the hike provided an opportunity to discuss the differences between Grizzly and Black bears, and territorial versus predatory attacks - which are difficult to discern, but costly to confuse. With a conservationist as his partner, David eschewed pepper spray, relying instead on yodelling to scare off bears.

Along the way, David mooted us returning to climb Mount Robson, but I pretended not to hear. As a cautionary tale, Edward Whymper made a couple more trips to the Rockies, which were increasingly comical and sad. In 1904, he announced his intention to conquer the supposedly impregnable Crowsnest Peak, which his guides climbed without him, while he recovered from a hangover. And, more alarmingly, he requested his outfitter to procure a young Stoney Indian boy - which his outfitter sensibly ignored. Meanwhile, the conqueror of Canada’s Matterhorn, James Outram bagged several more first ascents and moved out here permanently, going into property development with a shady business partner, who disappeared when their company went bust, leaving Outram in genteel poverty and disgrace. If you do come and climb in the Rockies, best quit while you’re ahead.

Photos by: David Lussier & Fiona McIntosh

Helpful Tips

- The best time to climb Assiniboine is between July and early September, but you should still be prepared for snow and storms.

- The standard North Face route is technically easy at US grade 5.5, although the length (1000m), weather, rock quality, exposure and consequences may conspire to make it feel more difficult.

- The nearest towns to the trailheads are Canmore and Banff. The closest international airport is Calgary (about 100km).

- We climbed with David Lussier of Summit Mountain Guides.