The plains trembled and the swirling, brown cloud of dust hovered as the wildebeest moved towards the Mara River - the Great Wildebeest Migration across the plains of East Africa had begun.

The migration is one of the world’s most spectacular displays of wildlife behaviour – a thrilling, intriguing and marvellous sight. At first, it is just a trickle, an advance guard of zebras and a few columns of wildebeest, crossing the Tanzanian border, spilling across onto the savannah plains of the Masai Mara National Reserve. The reserve which is in Kenya forms part of the continuous ecosystem with the Serengeti National Park in Tanzania. The trickle soon becomes a flood as the main body of the migrating herds comes rumbling in. For the next three to four months, usually between July and October, they stay in the Mara enjoying the fresh green pastures. They remain until the arrival of the short rains sometime in October/November, after which, they are drawn south once again to Tanzania.

As the masses of wildebeest move towards the river and gather on the banks, their urgency and hesitation can be sensed. The energy in the air crackles with anticipation and is gripping. Watching them, the wildebeest seemed to be mustering courage, as not even they appeared to know when to cross. It is impossible to predict as some arrive at the water and swim over immediately while others spend days hanging around grazing or turn back to where they have come from.

Unfortunately, the spectacle of the migration is misunderstood by many visitors which can lead to disappointment. It is not a mass of rushing herds as usually seen on TV and in documentaries. Most of the time the wildebeest spend time grazing and gradually moving forward towards the numerous water crossings. It takes time and patience to see them start lining up in columns and some luck to be at the right place at the right time when they decide to cross.

What’s in the name Masai Mara?

The Masai people named the plains the Mara as it means “spotted land” in the Maa language. It was a reference to the acacia glades that once freckled the grasslands before fire and elephants created today’s open vistas. The Masai Mara is the land of the Masai people. The Mara is not a national park but rather a national reserve belonging to the Masai people.

A year with a difference

Each year the wildebeest migration sparks a twin migration- the almost two million animals and then the tourists from around the world who flock to Kenya hoping to witness one of the natural wonders of the world.

This year has been anything but typical and the reserve, which was established in 1961, has been depleted of international visitors. The blow to Kenya’s economy has been devastating. Last year about 1 million tourists, mainly from the USA, Europe and China, visited the Mara and this provided much-needed income to the Masai community especially the informal sector that depends on tourists purchasing curios, handmade crafts and colourful Masai-shuka blankets.

Normally the plains would have been busy with game viewing vehicles, full of visitors, hoping to see a crossing and also possibly a lion hunt – but this year Kenyans had one of the country’s most sought-after wildlife experiences to themselves.

Tourism has struggled worldwide due to travel restrictions and Kenya is no different as its international borders were closed until the end of August 2020. This was a disastrous time for the lodges and tour companies – some simply closed but the more innovative ones recognised that they still had an untapped domestic market that had, possibly, been neglected during past migrations. By adjusting what they offered to satisfy the different expectations and needs of the local market many Kenyan citizens and residents were able to witness the migration for possibly the first time. This allowed businesses to survive with many camps being fully booked for the migration period.

We had not visited the Mara for nine years as we had found the experience disappointing and distressing. Having visited many different national parks in Kenya and other African countries we found the sight of tourists rushing around in safari vehicles, jockeying for prime positions at the river-crossing sites combined with the harassment of predators, especially the cheetahs, showing little concern for the animals they came to see and ignoring the basic rules of the bush, too harrowing to tolerate.

It was refreshing and a privilege to experience the Mara once again as a peaceful wilderness and especially to see that the reserve management was enforcing their rules and penalising defaulters. The reserve had been closed for 4 months and in that time Mother Nature had time to heal. The animals seemed more relaxed and many dirt tracks had covered over with grass erasing the scars of the previous tourist season. Without the pressure of other vehicles, we were able to sit watching a serval stalk and kill a large rat before taking it to its lair. Lions were plentiful and sightings of cheetah strolling across the grasslands as well as leopard investigating a riverbank were delightful moments. With fewer vehicles around we revelled in the random and at times the chaotic activity of the wildebeest and were fortunate to share the experience of three, action-packed, river crossings with only two other vehicles, whereas in past years there could have been up to 100.

Great Migration River Crossings

The Mara River meanders for 360km and the animals can cross anywhere, so, although there are some well-known places, there is not a single crossing point and there are no guaranteed places to witness the dangerous and frenzied river crossings. During the migration, there are numerous daily crossings over the Talek and Mara Rivers. One of the misconceptions of the migration is that the crossings can be predicted and are always at set river points. At some places, there are just a few individuals, while others see a mass of animals moving without a break for hours.

Waiting at the water’s edge we felt excited but also anxious as we knew that the time frame for the animals taking the plunge into the water would always be critical. Along with the snapping jaws of the crocodiles, there is also the ferocious current of the Mara River which often ends more lives than the predators. Large numbers of wildebeest drown during the crossings and their bodies provide a feast for the vultures and marabou storks. The crossings are by far the most dangerous part of the entire migration journey.

Suddenly, seeing thousands of wildebeest line up and move hastily across the plains towards the river, then the chaos of the crossing, we were in awe of and relieved for the strongest and most determined animals who reached the other side. Having survived the crossing some crossed back again in search of their young ones who perhaps hadn’t joined the group or were too nervous to cross. The atmosphere was one of amazement, excitement and encouragement as we watched the drama of the wildebeest leaping into the river, almost bouncing across the water, noisy, energetic, frantic, panic-ridden and chaotic. They were like ants, seemingly milling around with no direction but if fact with an instinctive objective and most with enough adrenaline-driven energy to get across.

But this scene also brought sadness as some animals were swept away by the river current and became wedged in the rocks and mud and we knew that there was nothing that could save them. These exciting, violent and dramatic crossings have been captured in many excellent films and documentaries, but being there and witnessing it from the river’s edge was an emotional and unforgettable experience.

What is the great migration?

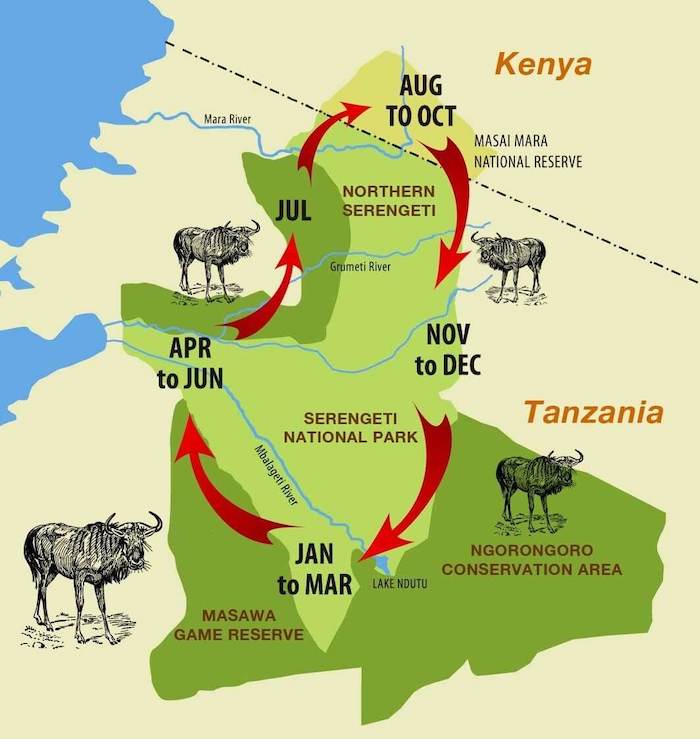

The migration occurs within an area that is known as the Serengeti ecosystem. It is not a single isolated event. Instead, the phrase describes the constant movement of over 1.5 million wildebeest, hundreds of thousands of zebra and smaller numbers of antelope such as eland, topi, impala, Grant’s and Thompson’s gazelle. The noisy, grunting army, chomp and trample the grass, rush across the Mara River in search of fresh grazing and provide predators with a season of plenty until the arrival of the short rains in October and November which draws them south to Tanzania again.

The Mara is the most northerly portion of the migration route and is the acclaimed location for the wildebeest migration due to its famed Mara River crossings. It has been named as one of UNESCO’s wonders of the world. This has led to some misunderstandings about the migration: it is an ever-moving column of animals following an age-old route that takes place throughout the year. The purpose of the movement is the search for pasture and water. When these vital resources are depleted in one area the animals move on to the next. Along the way, there is drama as animals are taken by predators but thousands more are born sustaining the circle of life.“When will the migration begin? “ - This is the question asked at every lodge in the Mara, every year. No one knows exactly when but by July the “answer” is already tramping across the plains as hundreds of thousands of hoofed animals come together and cross the Serengeti towards the new grass of the Mara.

The precise timing of the Serengeti wildebeest migration is entirely dependent upon rainfall patterns each year. It is unclear how the wildebeest know when or where to go but it is generally believed that their journey is dictated the weather. There is no way to predict exactly where the animals will be at any given time during their journey.

What triggers them to muster the energy to begin a 1000km round trip through two countries, across plains with lion and leopard waiting for them and the treacherous river crossings with crocodiles? Around 250 000 dies along the way, lost to predators, disease, fatigue, starvation and thirst even when there is still plenty of food around on the rolling plains of the Serengeti. But, somehow, a few seem to sense it’s time, perhaps there something in the air and just like that they get up and go and the largest terrestrial migration of animals on earth begins. Why, when most wildebeest in Africa are non-migratory do the animals in the Mara-Serengeti ecosystem risk so much in one mad trip?

It remains a mystery largely but some scientists believe it is to do with the chemistry of the grass. The herds are attracted to higher levels of phosphorous, calcium and nitrogen which changes in response to the rains. So perhaps the animals are just following their taste. It could also possibly be instinct, as for aeons the wildebeest have been following this route across the plains of East Africa

Great Migration calendar

Although there is no beginning or end to the migratory circuit – -it seems reasonable to call the birthing season, around end January/early February, the start of the migration. In mid-March, the mothers have calved and thousands appear happy milling around the rolling plains of the Serengeti. With the abundance of vulnerable young calves, it also means that predators are numerous and hunting is easy.

During April the herds begin to drift north-west towards the fresher grass of the central Serengeti, bringing thousands of zebra and smaller antelope with them. By May the columns of wildebeest stretch up to 40km and the mating season begins towards the end of the month, with the males battling head to head during “the rut” Throughout this time the journey continues at a leisurely pace with the wildebeest, zebra and gazelles grazing as they go along.

In June the dry season usually begins and by July they have been trekking across the plains for 3 months but still have the final hurdle of the rivers to confront, which are the most dangerous parts of the journey.

At the end of August, most of the animals have faced the challenge of the Mara River crossing and are spread throughout the Mara enjoying the nutrient-rich corn coloured grasses that stand tall enough to hide a prowling lion.

During September and October, the main chaos has ended and the migration gradually moves eastwards. However the wildebeest must once more prepare to cross the Mara River for their return journey southwards. The plains are bare by the time the wildebeest return south at the end of the dry season with the lush grasses reduced to yellow stubble by millions of mouths and hooves.

During November the storm clouds gather in the distance, they sniff the air and start heading back to the Serengeti National Park in search of fresh green meadows.

By January they have completed the southward trek, with the new grasses lush and inviting in the deep south of the Serengeti and the cycle continues as the calving season begins once again. As if they have no memory of the dangers ahead they still go year after year on their migration circuit.

What is the future for places like the Masai Mara National Reserve?

Despite the development of possible vaccines, the future is still unclear on when or if the world will return to anything like the past. There are so many questions that need to be addressed. Will the reduced income from tourism lead to the loss of national reserves and parks and an increase in poaching as communities struggle financially? Can natural wilderness areas and wildlife conservation be managed and funded more appropriately rather than from mass tourism?

Hopefully answers will be found so that our children and grandchildren can also experience the magic of the world’s natural wonders such as the Great Migration.