Tortoises are some of our most fascinating fauna. The unique domed shaped carapace combined with their slow gate and unusual appearance never fail to attract attention to wildlife enthusiasts.

The unique biology of tortoises belies the fact that they face numerous threats including climate change, illegal poaching and wildlife trafficking, shrinking habitats due to development, habitat degradation and bad habitat management (e.g. Habitat fragmentation, overgrazing and uncontrolled fires). Currently over half of all terrestrial tortoises globally are classified as threatened.

A young leopard tortoise grazing on farmland

South Africa's diverse tortoise population

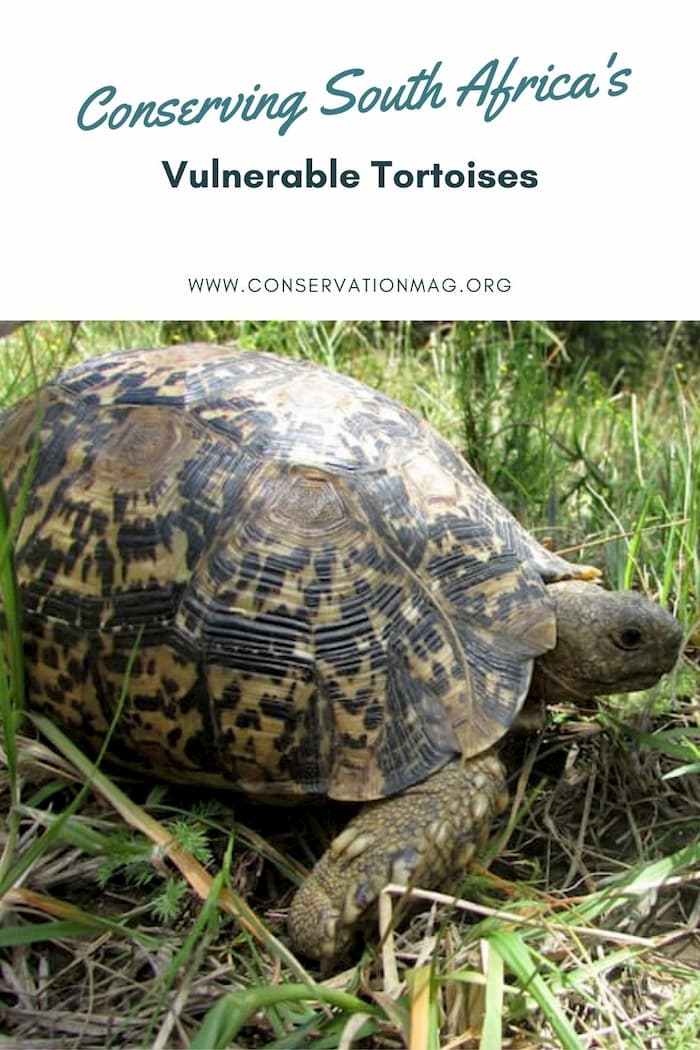

South Africa has the richest tortoise fauna in the world, with 14 species being present representing one-third of all tortoise species globally. Our species range in size from the largest, the leopard tortoise (Stigmochelys pardalis) that can be over 60cm in length and weigh up to 40kg to the smallest tortoise in the world, the speckled padloper (Homopus signatus) that never exceeds 10cm in length. In between these extremes, we have a range of species that exhibit fascinating differences in size, behaviour and ecology.

The Leopard and Angulate Tortoise

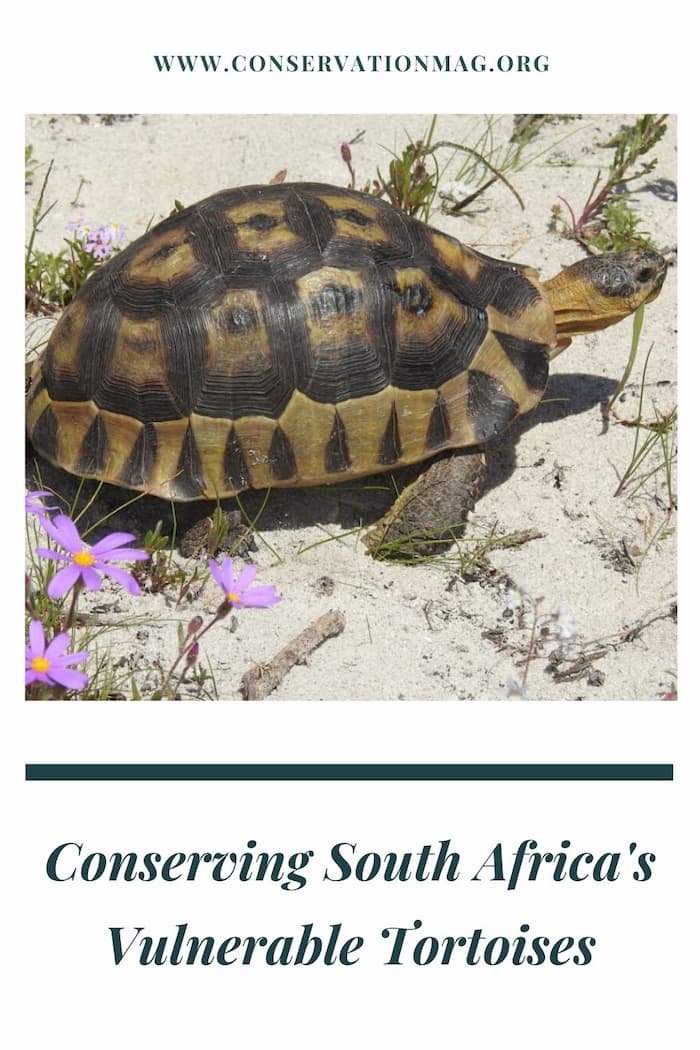

Our most common species are also our largest, the Leopard tortoise and Angulate Tortoise (Chersina angulata). Leopard tortoises are found in a variety of habitats, from thicket vegetation (e.g. Albany thicket, Bhisho thornveld, Great Fish thicket succulent thicket, to grasslands and karoo. They are docile and can become very habituated to human presence. Large individuals often become frequent visitors to grazing lawns on farmland and reserves and will occasionally also breed in the near vicinity of such areas. Young individuals can be very colourful with yellow and dark brown streaks on their scutes, giving them their common name. Leopard tortoise faces threats mainly from predators, climate change (e.g. drought and high temperatures) and habitat transformation.

This tortoise was tethered through a hole in its carapace and painted, an illegal method of keeping tortoises!

They are commonly kept illegally as pets although the extent to which this occurs is unknown. Occasionally individuals escape from inadequate husbandry conditions where they are still tethered or kept in an enclosure that harms the carapace. These individuals display signs of carapace damage or a hole that is drilled in the back of the shell where a chain or rope was attached. They are also still often eaten by people and electrocuted by wrongly installed electric fence lines. Their current conservation status is Least concern under the IUCN classification.

Tortoise eggs and young are vulnerable

Most tortoises in South Africa breed from spring to late autumn and all are egg-laying. Depending on the species egg clutches may be significant as in the leopard tortoise (6 - 15 eggs) or much smaller as is the case with Angulate tortoises where females only produce a single egg at multiple times throughout the year. The smaller padlopers and tent tortoises lay small clutches of 1 – 4 eggs. Prior to egg-laying, the female digs a burrow within which the eggs are laid and then covered again with substrate.

Adult tortoise armour

While adult tortoises are well protected against many predators (particularly larger species), their eggs and young are very vulnerable as predators such as other reptiles (e.g. monitor lizards) and mongoose, jackal, hyena and raptors will excavate and consume the eggs and young. In addition to these threats, small tortoises often disperse from the nest site and cross paved or dirt roads where they may be killed by vehicles. For the most part, predation is natural. However, it can become extreme in some cases where predator numbers are artificially high due to the presence of man-made food sources (e.g. refuse dumps).

An angulate tortoise male that has withdrawn into its carapace showing the elongated gular shield used in male combat.

An intriguing aspect of their breeding behaviour is that male tortoises will often fight for females. This is striking in the Angulate tortoises, a medium in sized (ca. 25cm) species, that are coloured yellow and dark brown. Males have a distinctive, unique elongated gular scale (underneath the head) that forms a long flat spike which is used to fight for territory and females. Angulate tortoise males will chase one another noisily in thick while fighting for females. During combat, the males will actively try to flip their opponent and will bite at the legs and other open skin of their opponents. Fights are not fatal. Angulate tortoises are unfortunately still illegally collected and exported although the actual quantities are unknown.

Tortoises are vulnerable due to the illegal pet trade

The beautiful colours of the geometric tortoise have resulted in many being illegally collected for the pet trade and combined with its shrinking habitat mean that is has reached the status of critically endangered. Other smaller species are naturally more vulnerable owing to their smaller size which creates a curiosity or novelty demand from collectors and presumably the ease with which they can be smuggled. These species include tent tortoises such as the Karoo tent tortoise and padlopers such as the greater padloper (Homopus femoralus) and Parrot beaked padloper (Homopus areolatus).

Small tortoise species such as this Parrot beaked padloper are tempting targets for illegal collectors.

Common species such as leopard tortoise and angulate tortoise are still traded although their wild populations appear healthy. The numbers of other species that are smuggled or collected remain unknown, but increased efforts to monitor this trade are needed. All tortoises are currently protected species and listed under CITES 1 or 2 categories as well as other forms of provincial legislation such as the Cape Nature Conservation ordinance of 1974 and National environmental and biodiversity act 10 of 2004.

The karoo padloper (Homopus boulengeri) is an endemic tortoise found only in more arid Western and South Western areas of the karoo in South Africa.

Other threats to tortoises

Some of the significant issues that threaten our tortoises are habitat transformation and management. Habitat contraction due to urban and agricultural expansion can result in local populations going extinct or being very vulnerable to poor habitat management, particularly in habitats that require well-controlled burning. Uncontrolled fires can be particularly problematic, mainly if they occur in areas where tortoise numbers are high. For instance, the numbers of angulate tortoises killed in a single large wildfire spreading through the west coast national park killed between an estimated 99000 to 28200 angulate tortoises!! A general reduction in the habitat of other species that occur at lower densities (e.g. Tent tortoises) is also considered a potential threat to their populations. Degraded habitats that lose the correct composition of different plant species can also further reduce its suitability for these reptiles. Finally, climate change is another threat to tortoise habitats that could significantly reduce the available habitat and increase the frequency of fires and droughts, which could further impact our land tortoise populations.

Main image by Adriaan Buys ~ Angulate Tortoise at West Coast National Park

Shop for a cause

Shop on amazon.com | amazon.co.uk