The vast, shimmering savanna, dotted with weather-beaten anthills, mountains, thorn trees and doum palms swaying on the banks of seasonal riverbeds, makes for a magnificent landscape. However, a battle for survival is taking place in this vast expanse of remote, pristine, yet arid terrain in the north of Kenya and isolated pockets of Ethiopia.

The Grevy’s zebra is so rare that they are listed as an endangered species on the IUCN (International Union for Conservation of Nature) red list of threatened species. From a global population of 15 000 in the late 1970s, there are now just over 3000 remaining. Over 90% of these live in northern Kenya.

As hardy and adapted as they are, Grevy’s zebra is one of Africa's most endangered large mammals.

The situation is dire, but fortunately, something is being done about safeguarding these majestic animals by the Grevy’s Zebra Trust, which works in partnership with pastoralist communities in northern Kenya to conserve and grow the Grevy’s zebra population.

Where did the name Grevy come from?

In 1882, Menelik II, the Emperor of Abyssinia (now Ethiopia) gifted a zebra to the president of France, Jules Grevy. The French zoologist, Emile Oustalet, realised that this type of zebra was different from other zebras and named the species after President Grevy.

- Scientific name: Equus grevyi

- Swahili name: Punda milia

- Also known as the Imperial zebra

What makes Grevy’s zebra unique?

Grevy’s zebra is the largest of the zebra species. Like their relatives, plains/Burchell and mountain zebra, they are native to Africa and are very closely related to horses and asses. They all have distinctive black and white stripes and share the same genus, Equus.

Grevy’s zebra are easily recognisable from the more common plains zebra by several features. Most noticeable are the close narrow stripes, white belly, a black dorsal strip that runs the length of their back and striking black ear markings on their large, conical ears that stand upright and alert. This, combined with a long neck, a large head and bolder stripes on the chest and neck extending through the mane, which makes the neck appear thicker, gives them a mule-like appearance.

Grevy's Zebra behaviours and social structure

Although Grevy’s zebras are social animals and live in herds, they have much looser social structures than plains zebra. Grevy’s form groups that can change daily and within the herd; dominance is, to an extent, non-existent other than the territorial male's right to the breeding female. Mothers and foals often stay together in nursery groups, although foals do not always travel with their mothers and might stay with several other foals watched over by an adult. Young males also form loose bachelor herds. They do not migrate; a stallion’s attachment to his land and the mare’s attachment to her young are the most stable relationships.

Why are Grevy's Zebra threatened?

They are highly mobile grazers and are beneficial to other grazers because they clear off the tops of coarse grasses and can digest many types and parts of plants that are difficult for other herbivores to digest. Despite their flexibility, a ribbon of water is a lifeline to these wild animals in a land of climatic extremes. They will only migrate to grazing lands within reach of the water.

Since 1977, Kenya has banned hunting them, but these zebras still compete with people and livestock for grass and water. Although they are protected in Ethiopia, poaching at times, with semi-automatic weapons, is still a concern as they are primarily hunted for their striking skins and occasionally for food.

Grevy's Zebra Range

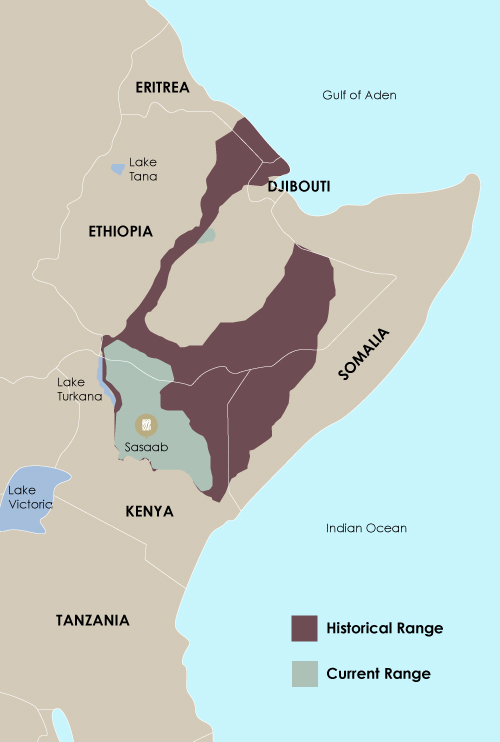

Grevy’s zebra has had one of the most substantial range reductions of any African mammal. Historically, they were found across the Horn of Africa, including Djibouti, Eritrea, Somalia and Sudan.

Now they are found only in Kenya and Ethiopia.

International Zebra Day

A consortium of conservation organisations, such as the Conservation Biology Institute and Smithsonian’s Natural Zoo, founded International Zebra Day, observed on January 31. This day is celebrated yearly to raise awareness of the three zebra species and what can be done to protect and conserve them from further decline.

About the Grevy’s Zebra Trust

There is, fortunately, an organisation focused solely on conserving this species. The Grevy’s Zebra Trust (GZT) was established in 2007 and works to conserve the Grevy’s zebra in partnership with communities. They are an independent wildlife conservation Trust registered in Kenya and the only organisation dedicated to saving the endangered Grevy’s zebra. It works with elders, warriors, women and children from the Samburu, Turkana and Rendille ethnic groups to increase conservation awareness and encourage positive attitudes towards the species and their habitat.

For more information, visit: grevyzebratrust.org

As a dust devil crosses the dusty plains and the sandy soil spins into the air in the arid wilderness, one can ponder that these endangered animals can only survive when their habitats are no longer threatened.