No one had ever successfully raised five pangolin pups and released them in the wild. Wildlife experts say they’re virtually impossible to rear in captivity. Easily startled, they’ll stop feeding and curl into a protective ball without warning. Their infant formula has to be mixed just right, and once they pass that hurdle, many don’t survive the transition to solid food; others simply fail to master the skills needed for survival in the wild.

Maria is a pioneer in understanding the needs of pangolins, building on decades of work with the cape pangolins native to southern Africa. Cape pangolins stick to the ground and are ten times the weight of the tree-dwelling white-bellied pangolins she’s working to save, but Maria’s patience paid off when their first white belly was tagged and released into a private reserve miles outside the African megacity of Lagos.

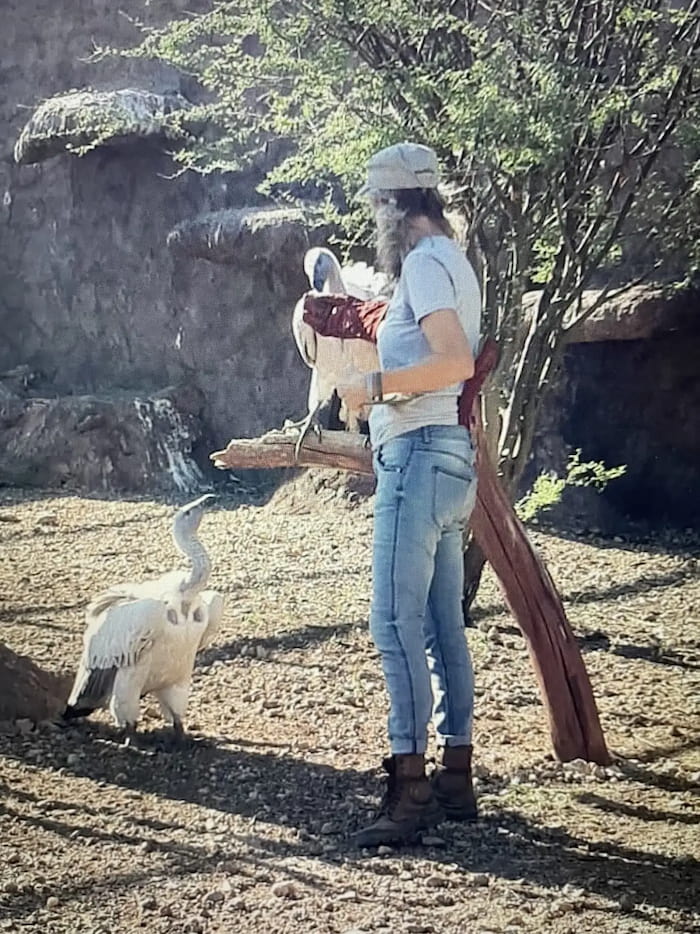

Maria, just outside of Lagos

It’s a promising outcome in the efforts to save these poorly-understood animals being poached into extinction. The animals she’s working to save have been rescued from local bush meat markets, torn from their mothers and discarded because they’re too small to be of any value to the traders.

Throughout West Africa, pangolins have long been prized as bush meat. But practitioners of Chinese traditional medicine pay top dollar for the animal’s scales, which has increased demand far beyond levels considered sustainable. Lax enforcement and lower penalties have led traders from neighboring countries to ship their pangolin scales overland to Lagos, where they are exported by the containerload. In one seizure alone, authorities in Lagos seized 7.1 tons of pangolin scales–representing an estimated 15,000 animals–in August 2021. WWF estimates one pangolin is killed every three minutes.

A native Californian, Maria has spent the last three decades in Namibia, a country in Southern Africa few outsiders can point to on a map, saving animals most people have heard of. Her trip to Nigeria was meant to be temporary; and indeed, it was–she had to rush home when she contracted malaria, a disease virtually unheard of in her adopted home, whose climate resembles that of the high Arizona desert. But just before heading home, she received a tantalizing job offer: she would relocate to Nigeria permanently to establish and operate a pangolin rescue center in a plot of virgin West African rainforest. The timing was perfect.

Who is Maria Diekmann?

Three decades earlier, working on the seventy-first floor of a Chicago law firm, Maria Diekmann was restless. She had dreams of entering politics one day. “I wanted to go to law school and not because I wanted to be an attorney, but because I wanted to get into politics. One side of my family was very involved in politics,” she said. Her grandfather was the late Earl Warren–former governor of California who would later become one of the most respected Supreme Court Justices in American history.

Like-minded friends and former classmates had joined the State Department, with an eye toward focusing on the crumbling Soviet Union. Maria felt she was a few years too late for that. Instead, she turned her gaze toward South Africa. The year was 1989; future president Nelson Mandela was still in jail, and on college campuses across the United States there were ongoing protests against Apartheid.

“Mandela was still in jail…but you know, the cracks were already showing. So I decided to come to South Africa for nine months,” she said. It seemed like a good way to gain unique experience that would eventually help with law school. She gave notice, packed her bags, and took a flight to a country she knew very little about.

Half a world away with her two suitcases, Maria had no idea where she would stay. The hostel a woman on her plane suggested was packed; so she ended up staying with a woman from her church. Her host’s son if Maria could drive him to neighboring Namibia, at the time still known as German South West Africa. South Africa still occupied the territory, in defiance of an International Court of Justice ruling two decades earlier; but by 1989, Namibia’s UN-supervised transition to independence was in full swing.

But life had other plans for Maria. “I came up to Namibia thinking that I would just check it out before independence. I thought it would be sort of a three-week thing, and then on the second day, I met my future husband…a hang glider pilot.”

With savannahs that stretch forever, punctuated here and there by odd rock formations, Namibia was–and is–a nature lover’s paradise. It is home to Etosha national park–half the size of Switzerland; the Skeleton Coast with its shipwrecks and uniquely adapted desert lions and elephants; and the world’s oldest desert that is oddly brimming with strange life forms, and a human population at independence of just 1.5 million.

Namibia. Photo by Thomas Brouns

She married and moved to the Diekmann family’s remote farm, which bordered the red rock cliffs of Waterberg Plateau Park, a national park and haven for hundreds of rare birds and animals. The Diekmanns were conservation-minded, in keeping with Namibian priorities–its new constitution would be the world’s first to mandate care for the environment.

For years, the family had annually surveyed the Cape griffons that nested in the cliffs separating the park from their property. They estimated no more than a dozen remained. And that’s how the passion for conservation took hold with the Diekmann family’s newest member.

Maria dreamed of creating an animal rescue center with the Cape griffon as its flagship species. She contacted a number of conservation experts for advice on how to get started. But with no prior experience, she didn’t get much help.

“I think everyone was a bit skeptical, you know? And they kind of patted me on the head and said, ‘Oh, sure, sweetie. Do whatever you want.’”

But Maria found a surprise ally. Just ten years earlier, fellow northern Californian Dr. Lauren Marker had founded the Cheetah Conservation Fund (CCF) on a nearby property. Marker’s project caught the attention of Art Risser, the General Manager of the San Diego Zoo, and his wife Priscilla. The Rissers were in town to see the CCF and were staying at a guest house on the Diekmann farm.

“So he and I just got sitting one day, you know, sort of on my stoop, and I can still remember sitting on the cement…relaxing,” recalls Maria.

“And I said, ‘You know, we need somebody like you here, Art, to do this project because these griffons really need us.’ And I can still remember exactly his words. He just said, ‘No, we don’t need somebody like me. They need somebody like you.’”

“You just need the support of people like me,” he continued.

Maria would learn later that Risser had been very involved in efforts to save the California condor, another endangered vulture. Weeks after meeting him, Maria founded REST — the Rare and Endangered Species Trust. Over the next decades, she would become one of the world’s leading experts on caring for some of southern Africa’s most vulnerable animals.

She initially focused on birds, and said she almost called the organization NEST, the Namibian Endangered Species Trust. But she knew from the start she wanted to help all animals.

Maria Diekmann, in the early days of REST, working with Cape griffons

Most tourists in southern Africa hope to catch a glimpse of the “big five:” the lion, leopard, rhino, elephant and African buffalo. But Maria focused on what she called “the forgotten five:” the dwarf python, the spotted rubber frog, the Damara dik-dik–a tiny antelope–and the Cape griffon. “I think the [African] wild dog was part of it for a while too, but then we dropped it,” she adds.

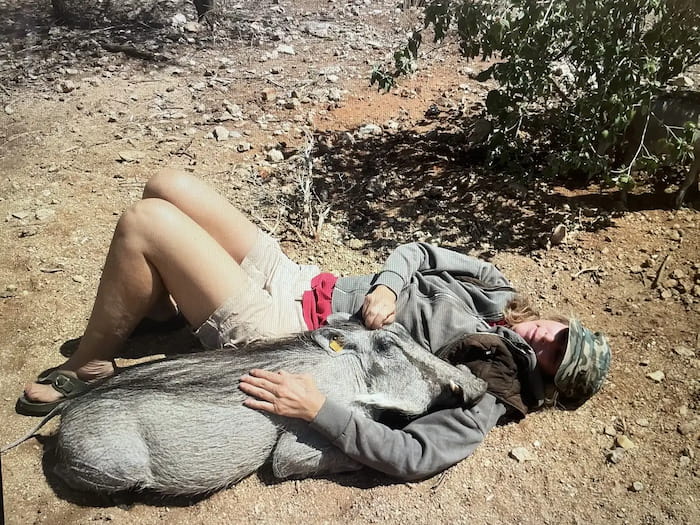

Maria with an aardwolf, the day before it is released

Maria meets her first pangolin

It would be more than a decade before pangolins entered Maria’s life in a meaningful way. She had developed a reputation at being the best at raising certain kinds of animals–mainly vultures and raptors; they were being cared for in an aviary on the property, which also included an education center and a vulture hide. Occasionally someone would bring her a pangolin from the field, but there was little institutional knowledge at the time on how to care for them.

“You tried to weigh it, and offer it some water–which it never took–and you put it in the car and drove it to the wildest area you could find, and you released it. In retrospect, probably almost the most wrong thing you could do.”

One day in 2014, a local shopkeeper, out of pity for the animal, a wildlife trader 400 rand–about $40–for a pangolin that had already spent three days in a cage. A board member from REST happened by the shop and suggested he bring the animal to Maria, who would know what to do.

Maria, with a warthog raised from infancy

What is a pangolin?

A white-bellied pangolin spends much of its time in the trees

Some climb in trees, but others spend their lives on the ground, often scuttling along on just their hind legs, front legs tucked under their bodies, long tails extended to the rear for balance.

As the planet’s only scaled mammal, pangolins have a unique form of protection. At the slightest hint of danger, they curl into a tight ball until would-be predators give up and move on to easier meals. But those scales are also their biggest liability.

Despite the lack of any scientific evidence, practitioners of Chinese traditional medicine believe pangolin scales cure a wide variety of ailments. The growing demand for pangolin scales has pushed all four Asian pangolin species to the brink of extinction.

Importers have recently turned to the four African species as a new supply source. Over the last decade, according to the WWF, a million pangolins have been slaughtered for their scales. In 2019 alone, one was killed every three minutes. And because they are so shy and secretive, no one really knows how many remain in the wild.

To make matters worse, pangolins are extremely difficult to keep in captivity; in fact, some experts point out that if pangolins disappear in the wild, they will effectively become extinct. Their needs and habits are poorly understood, but thanks to efforts by passionate people like Maria Diekmann working across Africa and Asia, there is growing hope these creatures can be saved from oblivion.

REST is raided

When I called Maria to catch up, she was in tears. Her decades of work and reputation as an animal conservationist were no match for the intricacies of Namibian politics.

Operating an organization like REST in Namibia requires a general permit, plus a research permit, which can be very difficult to obtain. The process is so cumbersome and time-consuming, says Maria, that about half the wildlife organizations in Namibia don’t have current permits.

“Your application has to be three years before the year ends, so you usually do it in September, October, November latest. And then you don’t get your permit until maybe July, August, September. So they’re never, ever on time. So you’re used to not, you know, having your paper,” she said.

The regional office of Namibia’s Ministry of Environment, Forestry and Tourism told her not to worry, Maria said. She had submitted her application, and the lack of a paper permit from the ministry would not be an issue.

In October, 2020, Maria learned otherwise. She was working out the details of shipping Honeybun, another rescued pangolin she had raised successfully, to South Africa for emergency veterinary care.

“And suddenly, one woman in the ministry that works with permits just came down hard on me and started saying, ‘You’re operating illegally.’ So I said, ‘OK, what do I do to operate legally?’ So she said, ‘You hold on.’”

The next thing she knew, eight government officials–five from the ministry and three police–showed up at her home with a search warrant.

“They tell me they’re going to strip search me and I’m wearing shorts, flip flops and a T-shirt like I always do…And then a guy sits in my living room and he starts saying, ‘But your degree is in sociology and politics. You’re not even qualified to do this work.’” She asked herself how they even knew what her degree was in. Then, she says, they tore her house apart.

Ministry officials confiscated property, along with exhibits and preserved pangolins used for education and research–and left. No inventory, no receipts, no explanation.

Some of the items which would be confiscated without explanation

Maria says part of the problem is that the legislative framework that governs the type of work she and other conservationists do in the country hasn’t been developed in the 32 years that Namibia has been an independent country.

But there may be darker motives behind the raid. After three decades, Maria has a robust and loyal network of donors supporting her work. She suspects that others working in wildlife conservation assume if she gets shut down, that donor support will flow to them.

And the fact that none of the seized property was inventoried and no receipts were provided suggests corruption is also a factor. Over the years, there were pangolins she was unable to save. These were frozen for research or turned into educational exhibits so that people could examine these animals so rarely spotted in the wild. Maria estimates the scales still attached to these specimens are worth between $75,000 and $90,000.

Two years later, the Namibian government has still not allowed her to resume operations. When she called me, she had given up and was trying to transfer her remaining birds to other organizations that could care for them. She wanted to sell her remaining stuffed animal exhibits, which had been used to educate children about the importance of conservation, but the Namibian government told her they would become state property.

“Why should I forfeit it to the state? They’ve already taken everything from me; must they take these last things I can make some money with?”

So when Nigerian veterinarian Mark Ofua called Maria, his timing was perfect.

Nigeria calling

Pangolins are prized as bush meat in some parts of West Africa

Pangolins are rescued from a bush meat market in Lagos, Nigeria

In October, 2021, when he found himself in possession of five pups, he knew he was in over his head. He needed help. So he sent an SOS to the close-knit community of pangolin specialists–and Maria responded. Since the raid on her facility in Namibia had effectively shut her down, for the first time in more than a decade, she was without pangolins of her own.

But Maria’s expertise was with the Cape pangolin — a ground-dwelling southern African species. Even more challenging was the fact that no one had successfully simultaneously raised five pangolin pups. The pups in Lagos were white-bellied pangolins–one-tenth the weight of their southern African cousins; tree dwellers with completely different dietary and developmental needs.

Maria knew Namibian pangolins required a lot of space. The ants they feed on secrete formic acid to protect their colony. Given their concentrations in the colony, formic acid levels eventually reaches toxic levels, forcing pangolins to move elsewhere. To fill their bellies, they must roam as far as 15 kilometers per night among the endless anthills dotting southern Africa’s landscape, snacking as they go.

In Nigeria pangolins have much smaller ranges–just a few hundred meters. Scientists are still working to understand their behavior and what they require to survive.

Despite the differences between the species, Maria realized if she didn’t help, who would? So she boarded a plane and headed to Lagos.

Maria arrives in Lagos

After three decades of living in a rural part of one of the most sparsely populated countries in the world, Maria was overwhelmed when she first arrived in Lagos, the largest city in Africa, last October. The oppressive humidity and the noise–angry drivers honking cars, generators running 24/7–and air pollution generated by the concentration of machinery were new to her.

“Once I got used to all of that I found people very respectful, devoted to their religious beliefs, and very friendly and kind. The volume of pangolins coming in and potential for research was mind blowing,” she said.

More rain falls in Lagos in one month than often falls in Namibia–home to the world’s oldest desert–in an entire year. Air pollution in Lagos rivals that of other megacities such as Beijing or Mumbai. Maria said she knew she wouldn’t be able to live there year round. But for now, she was on a mission.

Like other mammals, newborn pangolins must be fed every few hours. At Saint Mark’s, Maria explained, they had a powder formula that had to be mixed before every feeding. Terrified, the pangopups would curl tightly into a ball, making feeding impossible. Maria’s first task was to gain their trust so they would relax.

“So you’ve got to sometimes force their little mouth open and then you’ve got this syringe with a really small teat at the end of it and you sort of squirt drop by drop into their mouth so they don’t choke or aspirate,” she explained. “It’s a really long, hard process.”

Feeding one pup took her anywhere from 30 to 45 minutes.

“So you’re feeding them through the night. If you’ve got more than one, you get in a cycle that revolves a little bit too quickly sometimes. So I had five. So by the time I’d finish feeding, I’d have about an hour to sleep and then I would start the whole cycle again,” she added.

Baby pangolins must be fed every few hours to have a chance at survival.

Even the concentration of the formula was a challenge, and completely different from what Maria used for the Cape pangolins “ Maria said suddenly three of the pups would get sick, and she’d have to diagnose what was happening on the fly. Talking to other pangolin providers and learning from their mistakes and successes enabled her to titrate the strength of her formula and keep the pups not just alive, but thriving.

As they aged, Maria gradually reduced the frequency of feedings to just once or twice a day. Finding the right balance is important, she said. “You’ve got to make sure that they don’t get too overweight because that hurts their heart and their liver and their lungs. You know, diabetes, all sorts of things, just like people have.”

Their transition from milk to solid food was another critical point in keeping the pangopups alive. Maria is still searching for the ideal solution, one that can also be used for rehabilitation. When pangolins reach seven to nine months, and weigh about a kilogram, they are ready for release. And as tree-dwellers, they must be strong enough, and skilled enough, to climb trees.

Maria worked with Ofua to design a room that was essentially a jungle gym for pangolins–outfitted with huge tree branches for them to practice on. “Because they’ll often hang from the trees too, so they’ll hang and sleep. I’ve got funny pictures of them doing funny things in the trees. When they’re little, they have absolutely no coordination,” she said.

White-bellied pangolins must learn to climb, in addition to other skills, before being released into the wild.

Working around the clock, Maria said they saved three of the initial five pangolins. She remembers the joy of releasing her first one in a private reserve called the Emerald Forest. But more kept turning up in the wet markets, and by December, she says they were raising nine pups. But that’s when she contracted a life-threatening bout of malaria and was medically evacuated back/home to Namibia.

Before that happened, she met Professor Akin Abayomi–the owner of Emerald Forest.

The Emerald Forest

Akin Abayomi is Lagos’s State Health Commissioner. He’s a medical doctor, but he refers to himself as an environmental activist/conservationist. He combines his degree in wilderness management with medicine to practice what he calls “environmental health, or the ‘one health’ paradigm.”

“Human beings are only as healthy as the environment in which they live,” he said. Among the consequences of environmental destruction, he includes “events like COVID or Ebola or Lassa fever, or anything that jumps from the wilderness animals in the wilderness to human beings.”

Since 2002, Abayomi and his two sisters have worked to preserve their family’s land–a 400-acre plot of virgin forest near Lagos. They successfully convinced communities in the surrounding farmland to take an active role protecting what remains of the native ecosystem. He worries about what will happen if the current rates of deforestation continue.

“In another 10 or 15–20 years, we’ll be showing our children animals that are in museums or in picture books that don’t exist anymore.”

“Em” in the Emerald Forest, just post-release.

It was in that forest that Maria would release the first of the pangolins she successfully helped rear. When Abayomi met her, he was immediately impressed, describing her as a “passionate conservationist” who had already contributed much to African conservation. “I introduced her to what we were doing. And of course, automatically, there was a synergy,” Abayomi said

Pangolins will first get a “soft release” to see how they do; then they’re released for good. This is not the release Maria participated in, but another organized by Mark Ofua.

Abayomi asked Maria to join his conservation efforts and create a pangolin sanctuary in the Emerald Forest, and she immediately agreed. Back home in Namibia, she quickly recovered from malaria and began the task of transferring her remaining animals — the ones that would be unable to survive in the wild — to other wildlife organizations. Once that’s arranged, she’s packing her things and moving to Lagos.

I asked Maria why she changed her mind about living in Lagos full-time.

“Although physically the trees were enormous and the birds unidentifiable, I could hear the noise of nature again. Birds, primates, insects buzzing and rustling in the leaves,” Maria said. “It was then I realized I could make a home in the forest and save so many pangolins that needed our help.”

“And most importantly, train others to continue the work.”

Abayomi looks forward to her return. “I’m very excited that she’s agreed to come back and we’re putting everything in place for her to come back to the center,” said Abayomi. It’s a bright spot in an otherwise fraught international effort to curb illegal trade in the world’s most trafficked mammal.

All photos, unless otherwise noted, courtesy of Maria Diekmann