Every aspect of life has seen some impact of the COVID-19 crisis. Marine conservation charities are currently struggling to stay visible in a world turned virus obsessed.

Conservation relies on a constant stream of data. Monitoring of endangered species populations, and environmental dynamics, let charities know where to focus their attention. Publications and reports give weight to recommendations they bring to governments and communities. For many charities, 2020 will represent a blank spot in records. The impact this will have on future conservation efforts and research is unclear.

MWSRP tracks the lengths and injuries of a unique population of resident whale sharks

Maldives Whale Shark Research Program (MWSRP) is a charity that monitors a unique population of resident whale sharks in a marine protected area. For the first time since 2006, they will not be conducting surveys this year. This will be a real blow to both MWSRP and the Maldivian government, who rely on MWSRP reports to keep track of this charismatic species. “This is frustrating from a research perspective,” points out Richard Rees, the director of MWSRP, “there will be a significant loss of survey data.”

Citizen science is a popular way to engage the public in conservation while gathering data. Restrictions on movement are currently limiting the number of wildlife reports through citizen science channels. “Our hope is that as tour operators reopen, citizen science data will help to bridge the gap [in surveys] to some extent,” Richard from MWSRP told me. He went on to describe how they are currently delving into historical reports and social media posts to identify new sharks and movement patterns.

Although most direct monitoring of marine megafauna has been postponed this year, there are still some data streams available to researchers. Manta Trust organises the global research of manta and devil rays. They have been able to continue gathering some data thanks to partnerships with the essential fisheries industry. “Fishery observer programs that we're collaborating with are still operating,” stated Manta Trust Associate Director Joshua Stewart, “albeit at reduced capacity.” Manta Trust also uses advanced monitoring tools that will allow them to continue receiving data from animals. “Our acoustic tags will continue to tell us about presence and abundance of mantas at our study site,” Joshua told me, “even if we're not able to complete in-person monitoring.”

A manta ray encountered during whale shark surveys - MWSRP

Lockdown is having a more immediate impact for hands-on conservation. The Olive Ridely Project (ORP) is responsible for the rehabilitation of injured sea turtles in the Maldives. They are called in when turtles are hurt by boat strikes or entanglement. Ibrahim Shameel, the coordinator for the ORP in the Maldives, told me they ordinarily receive patients from all over the widely dispersed islands. Current restrictions on transport mean they can’t get injured turtles to their centres for treatment. On top of this, reduced boat traffic means they may be missing animals. “There is a good chance that we are missing quite a number of turtles entangled in ghost nets drifting across the Indian ocean,” stated Shameel.

An entangled green turtle in Ha.Kelaa, Maldives - ORP/Ibrahim Shameel

British Divers Marine Life Rescue (BDMLR) is an organisation that helps stranded whales, dolphins, and abandoned seal pups in the UK. They are considered essential workers. This means they can still get out to attend rescues, despite government restrictions on travel. However, they rely on the public to report stranded animals. “We’ve seen a decline in call-outs and some rescues being passed to other organisations,’ stated Paul Smith, the Area Coordinator of BDMLR for Tayside in Scotland. BDMLR works by mobilising a nationwide team of marine mammal medics. Paul pointed out that with some medics self-isolating, and training of new medics suspended, their numbers are currently thin on the ground.

Conservation work is always dependant on the goodwill and support of local communities. Paul from BDMLR described how he has been trying to keep in contact with the public remotely during the lockdown. “The way we work, a physical presence and friendly face on the scene are what many expect of us,” he stated.

Shameel from the ORP, and Richard from MWSRP, both pointed out that the communities they work with rely heavily on tourism for income. They worry that even once restrictions on movement are lifted, it will be difficult to pick up where they left off. Communities will need support to rebuild. “People are struggling from impacts to their livelihoods.” pointed out Joshua from Manta Trust, “I think it will be a learning experience for us in terms of how willing, and able, communities are to support conservation efforts when they become financially insecure.” When asked what their first steps would be once travel restrictions are lifted Richard said they would “support however possible the local community that we depend on.”

Many aspects of the economy have already suffered as a result of COVID-19. The charity sector has been particularly badly hit. “This is a fairly catastrophic scenario for our charity,” stated Richard from MWSRP. Their funding relied on revenue from volunteers making contributions during fieldwork. A cancelled field season has meant their entire staff has been put on unpaid leave. “We're continuing to exist only due to the willingness of our staff and extended associates to … work voluntarily,” stated Richard. “Voluntourism as a way to fund conservation will have been hit very hard. Yet it's crucial to the survival of grassroots efforts.”

An MWSRP outreach session

BDMLR has seen a similar drop in funding; “merchandise sales have sunk since people don’t have spare cash,” stated Paul. Their business model relied on sales and income from training new medics. “As a small charity we’re not on TV like others,” Paul told me.

The charities I spoke with have been working during lockdown to developed alternative sources of funding. Even after lockdown their positions remain uncertain. “As the world recovers, conservation organizations will most likely struggle to acquire funding opportunities,” theorised Shameel from ORP. Seeking new sources of revenue may be key to organisations survival, now more than ever.

An ORP outreach session pre COVID-19 - ORP/James Appleton

Social media campaigns and new merchandise have been organised to try to see them through the crisis. “We have also put time into sourcing new revenue generating mechanisms, which will bolster our current model.” stated Richard of MWSRP.

The importance of remaining visible online was a reoccurring theme. “We are still trying to keep our online presence, ensuring that we communicate our findings to the public,” Shameel, from ORP, told me. Richard, from MWSRP, echoed his sentiment “There is … a larger captive audience with people locked down and spending more time on the web.” He also described how they have been focusing their attention on areas they don’t normally have time for. “It has given us … an opportunity to focus on areas of our work that we can't always dedicate time to, for instance writing up papers.”

A rehabilitated grey seal pup is released in Scotland - Jessica Harvey-Carroll

The early days of lockdown saw false reports of dolphins in Venice and drunk elephants in China. More reliable sources have predicted temporary reductions to greenhouse gas emissions as the global economy slows to a crawl. Speaking with conservationists I received mixed opinions as to whether the COVID-19 crisis would have any positive impacts on the environment. Some suggested that reduced disturbance may be giving animals a chance to recover. “This may well give rise to increased birth rates [of seals] and increase sightings,” theorised Paul from BDMLR.

“I think any benefits of this crisis will be small and short-lived and could swing hard around to disadvantages” stated Joshua from Manta trust. The loss of income to local communities may lead to overexploitation when restrictions are lifted. This message was backed up by Shameel of ORP who pointed out that animals are under pressures from multiple sources, not related to direct disturbance by humans. “Global climate is still changing, unless significant changes happen, marine habitats and animals who rely on them will suffer.”

There are lessons to be learned from this crisis. This is true for conservation as in every other aspect of life. Already, conservationists are working tirelessly to ensure they can adapt to the new normal. Shameel from ORP told me how they were; “trying to engage more with the public in the Maldives as well as globally on some of the work we do.” Paul from BDMLR predicted that; “social distancing will be a huge factor in the way we need to develop how we work.” The true impact that this year will have on marine conservation is unlikely to be revealed until the dust has settled. Joshua from Manta Trust told me “The longer [the crisis] goes on, the more dramatic the impacts will become as we start to lose capacity and continuity.”

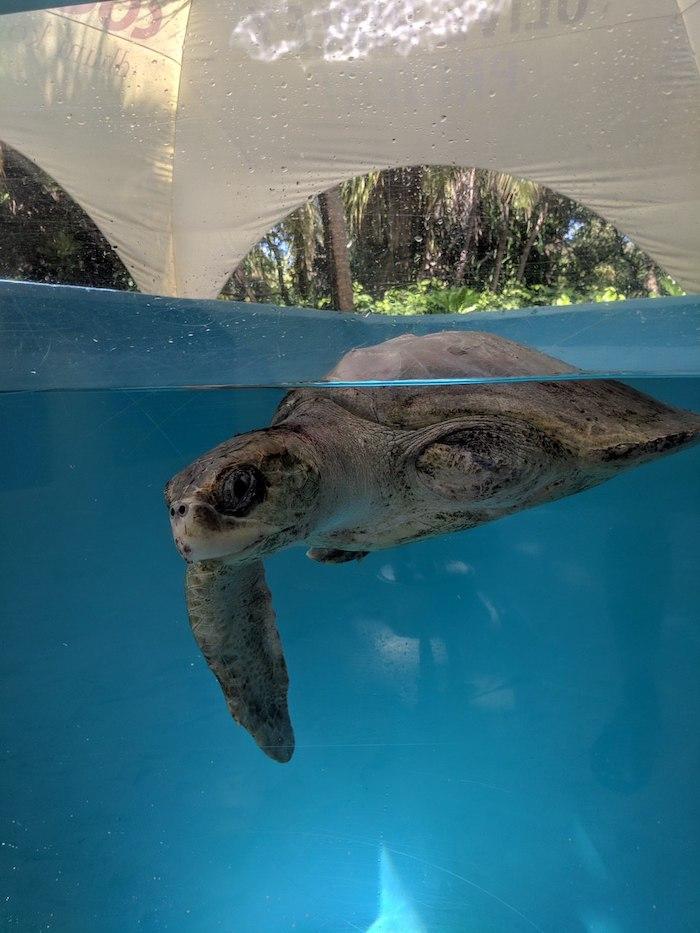

A patient in the ORP rehabilitation centre - ORP/Ibrahim Shameel

The challenges we expect to face in the coming decade are likely to have been compounded by the events of 2020. “Don’t forget that the planet is still suffering its own catastrophe,” Paul from BDLMR told me, “The planet, and nature, need you even more than ever.” The threats to our oceans remain unchanged as humanity has lived through this crisis. To protect our environment, we’ll need the efforts of charity organisations. These are propped up on a tenuous foundation of public support and grassroots engagement. Significant challenges lie ahead. Hopefully, marine conservation can benefit from the global mindset, and unity of purpose established overcoming the unique events of 2020.

If you are interested in supporting marine conservation efforts visit the Manta Trust, MWSRP, ORP or BDMLR websites to find out more.

Main Image - A stranded common dolphin is refloated and reunited with its mother in Scotland by Jessica Harvey-Carroll

Shop for a cause

Shop on amazon.com | amazon.co.uk