The thundering herd, the frenzied shoal, ‘Nature red in tooth and claw’. Observing first-hand great wildlife migrations is to watch the real ‘Survivor’ show, raw and uncensored. For the stampede of the wildebeest between the Serengeti and Masai Mara, the wife and I hung beneath a hot-air balloon, cameras cocked, drifting serenely above a savannah that was still and deserted, except for one lone, tatty lion who’d also pitched up a day too late. And on the annual Sardine Run, when dense silver shoals sweep up South Africa’s eastern seaboard pursued by dolphins, gamefish, seabirds and sharks, we repeatedly backward rolled off the dive boat into a tranquil, sard-less ocean.

So, for our latest viewing of Darwin’s immutable laws, we decided to follow a migration that occurs within a confined space, every day. In a small lake in Palau, Mastigias papua etpisoni - aka Golden jellyfish - follow the sun’s arc, so that micro-organisms living within them can photosynthesise, providing their gelatinous hosts with energy. While numbers wax and wane, on a good day there might be several million Golden jellies migrating en masse, in what’s called a ‘smack’. Best of all, this unique subspecies hasn’t bothered to retain a painful sting, allowing humans to swim alongside. What could possibly go wrong?

Well, if you’re starting from Cape Town, Palau is not the most convenient destination: nearly 13,000km, a couple of overnight flights and seven time zones away. This independent republic in the middle of the Pacific Ocean numbers over 300 islands and 18,000 inhabitants – though most live on just two, linked by a bridge spanning a few hundred metres. The archipelago’s ancient history is vague and blurry, though apparently not much happened. We wandered jetlagged around a field of stone monoliths, randomly scattered as if the workers had suddenly downed tools. And we slogged up to a traditional chieftain’s hilltop hut, that resembled an A-frame garden shed decorated by a rude child.

Indeed, Palau remained largely unknown and unbothered till the late 19th century, when in short order it was occupied by the Spanish, sold to the Germans, then grabbed by the Japanese. Rusting tanks and artillery entangled in vegetation betray the Land of the Rising Sun’s aggressive Pacific plans, while neglected memorials bear testament to the fierce fighting and 14,000 Japanese killed here during WW2, when the Americans cleared them out. However, my favourite landmark was Palau’s purpose-built capitol, Ngerulmud (‘the place of fermented angelfish’). Boasting tall Grecian columns and a dazzling white dome, it was modelled on Washington D.C., opened in 2006 and – with less than 300 residents in the scattered nearby homesteads - ranks as the world’s least populated capital city.

But Palau’s lure is not its city vibe or cultural heritage, but rather what goes on under its waters. A 45-minute boat ride took us out to the reef off Ngemelis Island, where we donned SCUBA gear and dropped into the topaz blue. As we drifted along, a pair of turtles paddled by, a shark circled above, grumpy moray eels snapped from crevices, barracuda glinted like knives, a manta ray buzzed us, and an electric clam pulsated like neon lighting. The water was warm, the visibility extended further than my eyesight and, on the boat trip to our second dive site, a pod of dolphins surfed under the prow. Nonetheless, I was impatient to move on. I had a migration to catch.

More by Matthew

The boat slaloms through shallow channels between the Rock Islands - uninhabited limestone outcrops, shaped like mushrooms, densely vegetated, and undercut at sea level by erosion, so if we do capsize, we’ll struggle to get ashore. Fortunately, one of the larger isles is distinguished by proffering a jetty, plus a hut manned by two rangers who check our permits. Shaped like a letter Y and six kilometres long, Mecherchar Island contains 10 small inland lakes, including the eponymous one filled with jellyfish.

From the jetty, a rugged trail leads over a ridge and down to a lakeside pontoon and while the hike only takes 10 minutes, in this heat and humidity, that’s plenty. Fringed all around by thick forest, Jellyfish Lake is the size of two cricket pitches and 30 metres deep. Though it’s connected to the sea by submarine fissures, only a tiny fraction of its volume changes with each tide and so, having somehow got in, the jellyfish were stuck, causing them to evolve as a different subspecies to their marine relatives - including becoming harmless to humans.

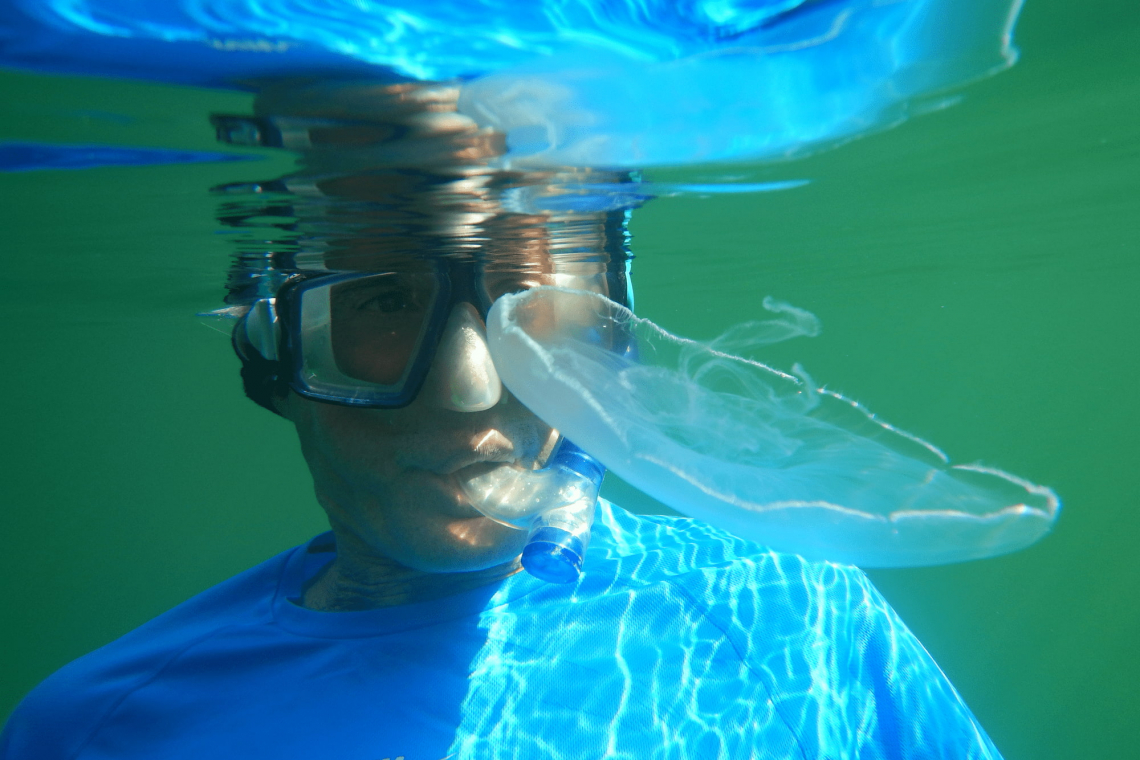

Indeed, the boot is on the other foot and we must rinse our masks and fins lest we’re unwittingly transporting chemicals or micro-species that might harm these delicate blobs. Likewise, SCUBA diving’s not permitted because the air bubbles upset them; though, just as pertinently, below 15 metres there’s such a high level of hydrogen sulfide in the lake, that it’s poisonous for humans.

Slipping into the turbid, tepid water, we fin out towards the middle of the lake, where the jellies cluster, away from the shore and predatory anemone tentacles that can snaffle them. Also known to lurk on Palau’s rock islands are saltwater crocodiles - though the last reported attack on a snorkeller was in 2012 and there’s never been one in Jellyfish Lake, so I’m just scaremongering myself. In fact, it's refreshingly peaceful out here, with just Fiona, me, a local dive master, plus hopefully several million jellies.

A photograph taken here by acclaimed National Geographic contributor David Doubilet, shows a snorkeller clawing through a swirling auric cloud - but while I’m innately unrealistic, I’m not expecting to capture a shot quite like that. Indeed, since organising this trip, I’ve been steadfastly ignoring disquieting rumours that the Golden jellyfish population is rapidly dwindling. The culprit is climate change, with a rise in the water temperature killing them off. And while this has happened several times before and the Golden jellies have returned, their reappearances have been getting briefer and the resurrected colony smaller. When our dive master warns we might not see any at all, I trust she’s just lowering our expectations.

We spend an hour in the lake, freediving till we’re exhausted, trying to photograph Moon jellies and failing miserably to capture David Doubilet-like images. Swimming back to shore, we finally spot two Golden jellyfish, like ageing screen stars trying to steal the show, and admittedly they’re much more photogenic than their lunar usurpers. Perhaps from this couple, Mastigias papua etpisoni will launch another comeback. Or perhaps they won’t. After all, time was called on the woolly mammoth, brontosaurus, dodo and 99.9% of all species to have lived on this planet. Evolution might be a wondrous thing, but you can’t rely on it personally, especially when planning holidays.